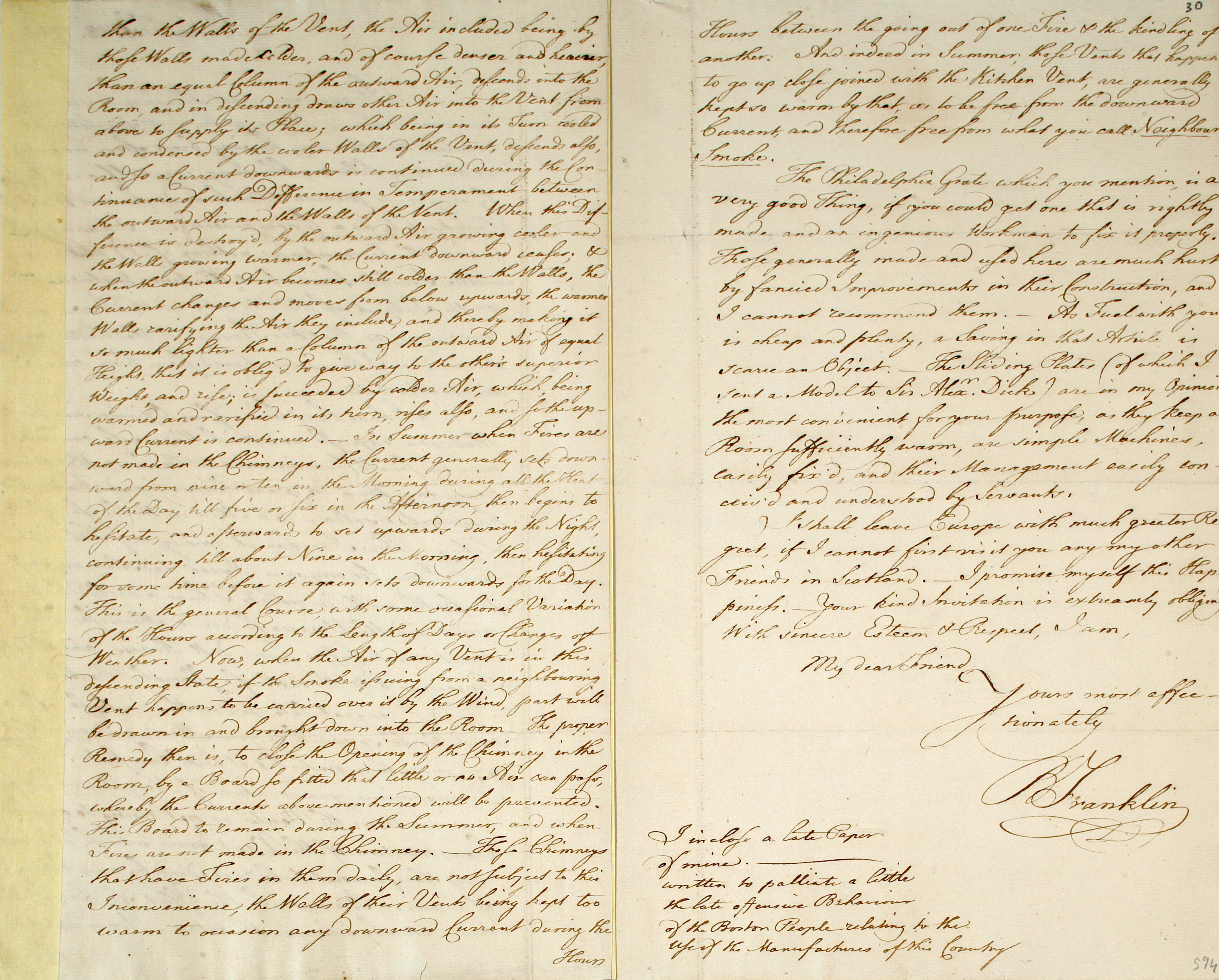

FRANKLIN, Benjamin (1706-1790). Letter signed ("B. Franklin") to Henry Home, Lord Kames ("My Dear Lord"), London 11 April 1767. Seven pages, 325 x 203mm, with the date additionally in Franklin's hand (fold separations neatly repaired, lightly toned in spots). [ With :] a fragment of the original address panel bearing his franking signature (“B Free Franklin”) and addressed in hand (separations, soiling), with intact wax seal. "America, an immense Territory, favour’d by Nature with all Advantages of Climate, Soil, great navigable Rivers and Lakes . must become a great Country, populous and mighty; and will in a less time than is generally conceived be able to shake off any Shackles that may be impos’d on her, and perhaps place them on the Imposers. In the mean time, every Act of Oppression will sour their Tempers, lessen greatly if not annihilate the Profits of your Commerce with them, and hasten their final Revolt: for the Seeds of Liberty are universally sown there, and nothing can eradicate them." Benjamin Franklin on the escalating conflict between Great Britain and her North American colonies. A lengthy and important letter to Lord Kames discussing the enactment of the Townshend duties, describing his examination before Parliament, and his prediction that if London did not tread lightly, colonial independence would be the ultimate result: “I was inclined to form (tho’ contrary to the general tongue) on the then delicate & critical Situation of Affairs between Britain and her Colonies, and on that weighty Point of their Union. You guess’d aright in supposing I could not be a Mute in that Play. I was extremely busy, attending Members of both Houses, informing, explaining, consulting, disputing, in a continual Hurry, from Morning to Night ‘till the Affair was happily ended. During the Course of it, being called before the House of Commons I spoke my Mind pretty freely.” Franklin then encloses “an imperfect Account” of the affair (not present), yet vastly superior to those found in “the Papers at that Time being full of mistaken assertions that the Colonies had been the Cause of the War, and had ungratefully refus’d to bear any part of the Expence of it.” For Franklin, part of the solution lay in his long-held belief in colonial union, a belief shared by his correspondent: “I am fully persuaded with you that a consolidating Union by a fair and and equal Representation of all the Parts of this Empire in Parliament, is the only firm Basis on which its political Grandeur and Stability can be founded.” By 1767, Franklin feared this concession by London would be coming too late: “The Time has been when the Colonies might have been pleas’d with it: They are now indifferent about it; and, if ‘tis much longer delay’d, they too will refuse it.” He is troubled by the arrogance of many in London toward colonial grievances: “Every Man in England seems to consider himself as a Piece of a Sovereign over America; seems to jostle himself into the Throne with the King, and talks of Our Subjects in the Colonies. Effective policy to collect revenue from the colonies could not be “wisely” implemented unless Parliament was “properly and truly informed of their Circumstances, Abilities, Temper,” Indeed it was that general ignorance of the daily economic and social realities of the North American colonies that resulted in laws that did more to loosen rather than solidify the bonds of empire. To Franklin, the solution was simple: seat ministers from North America in Parliament “This is cannot be, without Representatives from thence.” The Townshend Acts, Parliament’s second attempt to assert its right to tax the colonies, was part and parcel of the general ignorance of North American politics. Supposing that colonists merely opposed internal taxation, they would not object to customs duties, considered “external” taxation. Again they were wrong. Franklin believed “the contest is like to be revived.” He points to the Quartering Act as a particula

FRANKLIN, Benjamin (1706-1790). Letter signed ("B. Franklin") to Henry Home, Lord Kames ("My Dear Lord"), London 11 April 1767. Seven pages, 325 x 203mm, with the date additionally in Franklin's hand (fold separations neatly repaired, lightly toned in spots). [ With :] a fragment of the original address panel bearing his franking signature (“B Free Franklin”) and addressed in hand (separations, soiling), with intact wax seal. "America, an immense Territory, favour’d by Nature with all Advantages of Climate, Soil, great navigable Rivers and Lakes . must become a great Country, populous and mighty; and will in a less time than is generally conceived be able to shake off any Shackles that may be impos’d on her, and perhaps place them on the Imposers. In the mean time, every Act of Oppression will sour their Tempers, lessen greatly if not annihilate the Profits of your Commerce with them, and hasten their final Revolt: for the Seeds of Liberty are universally sown there, and nothing can eradicate them." Benjamin Franklin on the escalating conflict between Great Britain and her North American colonies. A lengthy and important letter to Lord Kames discussing the enactment of the Townshend duties, describing his examination before Parliament, and his prediction that if London did not tread lightly, colonial independence would be the ultimate result: “I was inclined to form (tho’ contrary to the general tongue) on the then delicate & critical Situation of Affairs between Britain and her Colonies, and on that weighty Point of their Union. You guess’d aright in supposing I could not be a Mute in that Play. I was extremely busy, attending Members of both Houses, informing, explaining, consulting, disputing, in a continual Hurry, from Morning to Night ‘till the Affair was happily ended. During the Course of it, being called before the House of Commons I spoke my Mind pretty freely.” Franklin then encloses “an imperfect Account” of the affair (not present), yet vastly superior to those found in “the Papers at that Time being full of mistaken assertions that the Colonies had been the Cause of the War, and had ungratefully refus’d to bear any part of the Expence of it.” For Franklin, part of the solution lay in his long-held belief in colonial union, a belief shared by his correspondent: “I am fully persuaded with you that a consolidating Union by a fair and and equal Representation of all the Parts of this Empire in Parliament, is the only firm Basis on which its political Grandeur and Stability can be founded.” By 1767, Franklin feared this concession by London would be coming too late: “The Time has been when the Colonies might have been pleas’d with it: They are now indifferent about it; and, if ‘tis much longer delay’d, they too will refuse it.” He is troubled by the arrogance of many in London toward colonial grievances: “Every Man in England seems to consider himself as a Piece of a Sovereign over America; seems to jostle himself into the Throne with the King, and talks of Our Subjects in the Colonies. Effective policy to collect revenue from the colonies could not be “wisely” implemented unless Parliament was “properly and truly informed of their Circumstances, Abilities, Temper,” Indeed it was that general ignorance of the daily economic and social realities of the North American colonies that resulted in laws that did more to loosen rather than solidify the bonds of empire. To Franklin, the solution was simple: seat ministers from North America in Parliament “This is cannot be, without Representatives from thence.” The Townshend Acts, Parliament’s second attempt to assert its right to tax the colonies, was part and parcel of the general ignorance of North American politics. Supposing that colonists merely opposed internal taxation, they would not object to customs duties, considered “external” taxation. Again they were wrong. Franklin believed “the contest is like to be revived.” He points to the Quartering Act as a particula

.jpg)

.jpg)

Try LotSearch and its premium features for 7 days - without any costs!

Be notified automatically about new items in upcoming auctions.

Create an alert