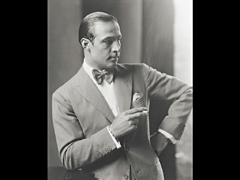

Edward Steichen Charlie Chaplin 1925 Gelatin silver print. 25.1 x 20.2 cm (9 7/8 x 7 15/16 in). Titled 'Chaplin', dated, annotated '258' by the photographer in pencil, annotated 'for V.F', 'Please return Edward Steichen ..', in an unidentified hand in pencil and ink on the verso.

Provenance Collection of Joanna Steichen; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York Exhibited Detroit Institute of Arts, Photographs from the Permanent and Private Collections, July–August 1971; Detroit Institute of Arts, The Camera and the Eye: Modern Photography 1925 to the Present, 1975 (each another example exhibited) Literature Edward Steichen A Life in Photography, London: W. H. Allen in collaboration with the Museum of Modern Art, 1963, pl. 180; On the Art of Fixing a Shadow: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Photography, exh. cat., National Gallery of Art, Washington, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1989, pl. 224; Edward Steichen Photofile, London: Thames & Hudson, 2008, pl. 50 Catalogue Essay The portrait by Edward Steichen offered in the present lot was taken during the rise and rise of the theatre movie age with “the average weekly movie theatre attendance in 1930 nearly equalling the entire population of the United States”. This was a time when the individual image of the film star was often linked to an iconic still rather than a scene from a film – the photographer provided the lasting essence, the embodied fantasy of Hollywood through portraiture. Steichen enjoyed his own personal taste of stardom through the pages of Vanity Fair. Vogue was the bible for fashion whereas Vanity Fair was the paper vehicle to inform us about who was who in the world of literature, film and art, planting these people in our long-term visual memory with a tenacious determination. Unlike Alfred Stieglitz Steichen did not mind taking portraits and being paid for them. He had supported himself long before his role at Vanity Fair, having set up a small studio on 5th Avenue in New York in 1902. Steichen always had energy, enthusiasm and versatility – as a young man, he had adapted readily to his move from fine art and the pictorial to the portrait and, in some ways perhaps, less control of his subject (he did not have the luxury of choosing who he would photograph during his magazine days). His craft changed substantially too, working initially with the sensual softness of the gravure (so many exquisite examples being featured in Camera Work) and then moving to the use of the silver gelatin process, until 1915 when he threw off his pictorial cloak to make sharply focused photographs. One ingredient which always remained constant was his use of light, the former natural softness giving way to the style seen in the portrait featured here, with its dramatic and highly controlled lighting. His re-invention of lighting meant he literally staged his subject giving immediate impact on the printed page. “I wanted to reach in to the world, to participate and communicate … to make photographs that could go on the printed page, for now I was determined to reach a large audience instead of a few people I had reached as a painter.” (Edward Steichen The Portraits, San Francisco: Art Museum Association of America, 1984) When Steichen met Charlie Chaplin both men were firmly in the lime-light; one year before this meeting, Chaplin had released The Gold Rush which we now recognise as one of his all-time classic creations. Steichen had become one of the most successful commercial photographers of his time – during his 13-year relationship with Condé Nast, there are only a handful of issues in which his work did not feature in. Through this long passage of portraiture, he found interest in all his subjects, but especially Charlie Chaplin: “Of course I had favorites. Chaplin was one. The first time he came to the studio, his secretary, who brought him there said, ‘Mr Chaplin has another appointment, so he can only give you twenty minutes’.” (Edward Steichen A Life in Photography, London: W. H. Allen in collaboration with the Museum of Modern Art, 1963, Chapter 8, n.p.) You would not realise for a moment looking at the final image of this relaxed and successful man, illuminated, standing free of his usual movie apparel, proud with dapper suit, hat and cane firmly in

Edward Steichen Charlie Chaplin 1925 Gelatin silver print. 25.1 x 20.2 cm (9 7/8 x 7 15/16 in). Titled 'Chaplin', dated, annotated '258' by the photographer in pencil, annotated 'for V.F', 'Please return Edward Steichen ..', in an unidentified hand in pencil and ink on the verso.

Provenance Collection of Joanna Steichen; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York Exhibited Detroit Institute of Arts, Photographs from the Permanent and Private Collections, July–August 1971; Detroit Institute of Arts, The Camera and the Eye: Modern Photography 1925 to the Present, 1975 (each another example exhibited) Literature Edward Steichen A Life in Photography, London: W. H. Allen in collaboration with the Museum of Modern Art, 1963, pl. 180; On the Art of Fixing a Shadow: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Photography, exh. cat., National Gallery of Art, Washington, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1989, pl. 224; Edward Steichen Photofile, London: Thames & Hudson, 2008, pl. 50 Catalogue Essay The portrait by Edward Steichen offered in the present lot was taken during the rise and rise of the theatre movie age with “the average weekly movie theatre attendance in 1930 nearly equalling the entire population of the United States”. This was a time when the individual image of the film star was often linked to an iconic still rather than a scene from a film – the photographer provided the lasting essence, the embodied fantasy of Hollywood through portraiture. Steichen enjoyed his own personal taste of stardom through the pages of Vanity Fair. Vogue was the bible for fashion whereas Vanity Fair was the paper vehicle to inform us about who was who in the world of literature, film and art, planting these people in our long-term visual memory with a tenacious determination. Unlike Alfred Stieglitz Steichen did not mind taking portraits and being paid for them. He had supported himself long before his role at Vanity Fair, having set up a small studio on 5th Avenue in New York in 1902. Steichen always had energy, enthusiasm and versatility – as a young man, he had adapted readily to his move from fine art and the pictorial to the portrait and, in some ways perhaps, less control of his subject (he did not have the luxury of choosing who he would photograph during his magazine days). His craft changed substantially too, working initially with the sensual softness of the gravure (so many exquisite examples being featured in Camera Work) and then moving to the use of the silver gelatin process, until 1915 when he threw off his pictorial cloak to make sharply focused photographs. One ingredient which always remained constant was his use of light, the former natural softness giving way to the style seen in the portrait featured here, with its dramatic and highly controlled lighting. His re-invention of lighting meant he literally staged his subject giving immediate impact on the printed page. “I wanted to reach in to the world, to participate and communicate … to make photographs that could go on the printed page, for now I was determined to reach a large audience instead of a few people I had reached as a painter.” (Edward Steichen The Portraits, San Francisco: Art Museum Association of America, 1984) When Steichen met Charlie Chaplin both men were firmly in the lime-light; one year before this meeting, Chaplin had released The Gold Rush which we now recognise as one of his all-time classic creations. Steichen had become one of the most successful commercial photographers of his time – during his 13-year relationship with Condé Nast, there are only a handful of issues in which his work did not feature in. Through this long passage of portraiture, he found interest in all his subjects, but especially Charlie Chaplin: “Of course I had favorites. Chaplin was one. The first time he came to the studio, his secretary, who brought him there said, ‘Mr Chaplin has another appointment, so he can only give you twenty minutes’.” (Edward Steichen A Life in Photography, London: W. H. Allen in collaboration with the Museum of Modern Art, 1963, Chapter 8, n.p.) You would not realise for a moment looking at the final image of this relaxed and successful man, illuminated, standing free of his usual movie apparel, proud with dapper suit, hat and cane firmly in

.jpg)

Try LotSearch and its premium features for 7 days - without any costs!

Be notified automatically about new items in upcoming auctions.

Create an alert