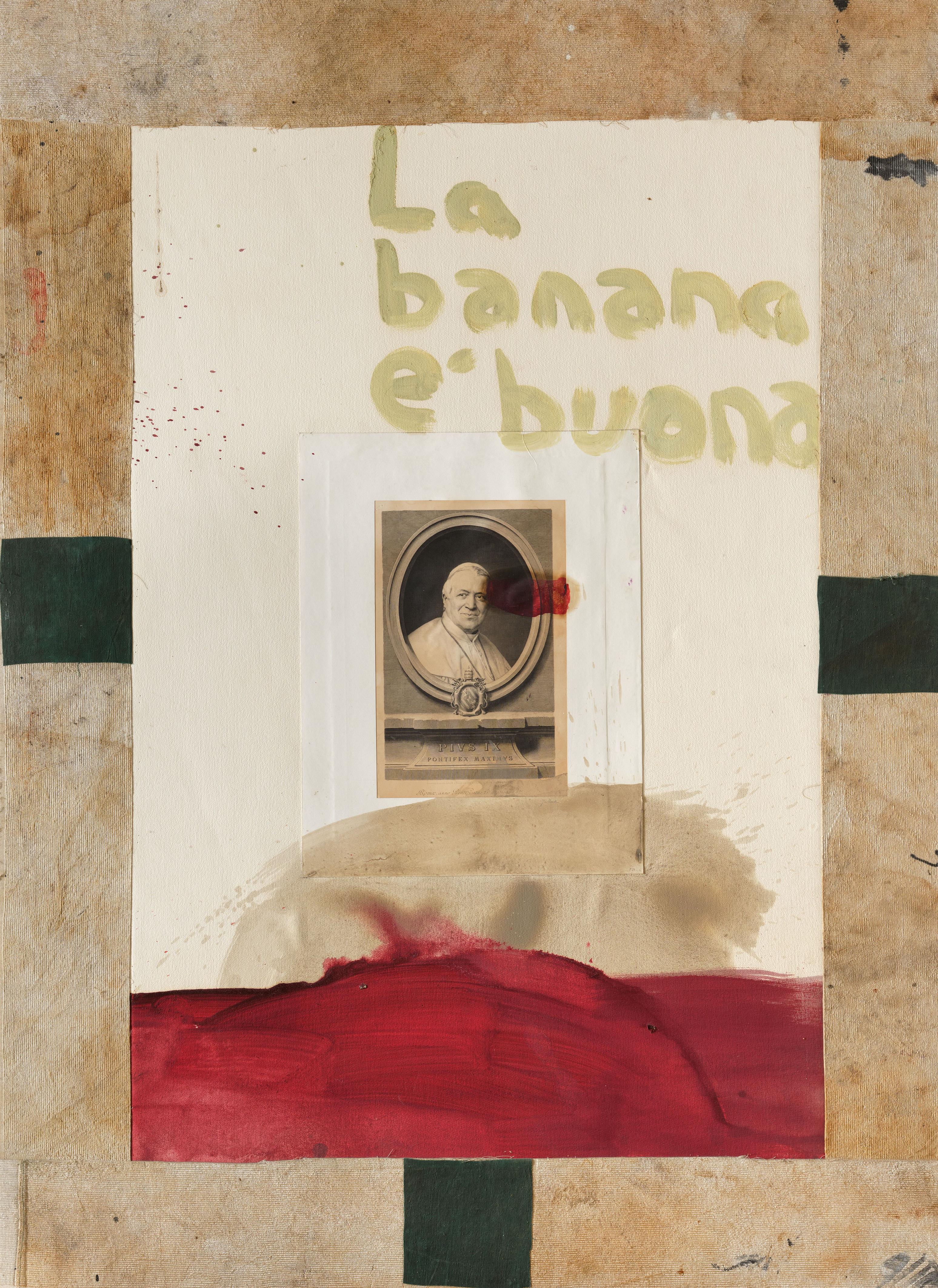

Julian Schnabel Sonanbul 2005 oil, wax, resin on digitally printed canvas 274.5 x 210.5 cm (108 1/8 x 82 7/8 in.) Numbered 'P05.0004' on the stretcher.

Provenance The Artist Robilant + Voena, London Private Collection, London Catalogue Essay ‘Just because there is an image of a spirit does not make the painting spiritual or about spirituality. That being said, it’s interesting to see them through the lens of a sacred iconography. But there’s a moment when figures melt and become paint. What I am doing is intervening, and watching an icon disintegrate into the ground and re-form, without a preconception of what the story is.’ - JULIAN SCHNABEL 2011 Julian Schnabel produces works in a variety of mediums that range from painting and sculpture to Oscar-nominated feature films. Emerging in the late 1970s as one of the leading figures in the Neo-Expressionist movement, Schnabel’s works represent a break with the conceptual tradition that had afflicted American art in the previous decades. In a return to figuration, Schnabel crowds his canvas with heavy gestural brush strokes, paint drips, found materials – most famously broken plates – and substances such as wax, in a collage-like layering process on the various materials that function as his canvases. Schnabel’s themes are as wide ranging as his materials. Sexuality, identity, suffering, redemption and death are all aimed at engulfing the emotional state of the viewer. The typically enormous scale of a Schnabel work is also an important component of its power, as aggressively confrontational as his public persona. Often including words and text in his works, Schnabel has stated that he embraces ‘the subjectivity of the written word and the many forms it can take, and the many different meanings that are possible to different viewers depending on where they are from.’ (Julian Schnabel in Conversation with Alex Gartenfield, Julian Schnabel Permanently Becoming and the Architecture of Seeing, Thames and Hudson, 2011, Pg. 43). Schnabel leaves it to the viewer to form connections and find meaning between his images and text. In this sense, his collages work in a similar way as the ‘Combine’ paintings produced by Robert Rauschenberg in the mid-late 1950s: Rauschenberg’s conglomerations jostle newspaper clippings, paint and other found objects in a ramshackle assembly, each element vying for our interpretation. However, while Rauschenberg’s works were produced in the spirit of anti-art and absurdity, Schnabel’s are very much a celebration of art and the process of creation. The present lot began with a digitally printed image of a Japanese woodblock print of a courtesan; the figure is masked behind dripping layers of oil, wax and resin, weathered, attacked, even submerged in these accretions. The meaningless yet somehow allusive word ‘sonanbul’ – perhaps a misremembering of the French somnambule, sleepwalker – glides at a gentle diagonal above her head, hinting at significance without offering coherent meaning: there is an oblique yet eloquent dialogue between residue and underlying structure, the print’s original decorative frame made poignant and ruined. Schnabel’s exaggerated, chaotic surfaces are as loaded with emotion as with materials, but they are not heroic in the sense of history painting; they signal a change in attitude that emphasizes the emotion of expression. In 1986, Schnabel talked of the rejection of Conceptualism and Minimalism through a return to painting and figuration by artists in the late 1970s and 1980s as a seismic change. ‘There has been a shift in the emphasis of art. A break with the American tradition of painting. That break will define the end of this century. It is an essential break with the role of the heroic. A break with art’s need to be American or European.’ (Julian Schnabel in Conversation with Alex Gartenfield, Julian Schnabel Permanently Becoming and the Architecture of Seeing, Thames and Hudson, 2011, p.24). As Mick Brown writes, this was not an easy stance for Schnabel to take. ‘Critics vilified him as a huckster who personified the bloated, mercantile avarice of the age. Robert Hughes was par

Julian Schnabel Sonanbul 2005 oil, wax, resin on digitally printed canvas 274.5 x 210.5 cm (108 1/8 x 82 7/8 in.) Numbered 'P05.0004' on the stretcher.

Provenance The Artist Robilant + Voena, London Private Collection, London Catalogue Essay ‘Just because there is an image of a spirit does not make the painting spiritual or about spirituality. That being said, it’s interesting to see them through the lens of a sacred iconography. But there’s a moment when figures melt and become paint. What I am doing is intervening, and watching an icon disintegrate into the ground and re-form, without a preconception of what the story is.’ - JULIAN SCHNABEL 2011 Julian Schnabel produces works in a variety of mediums that range from painting and sculpture to Oscar-nominated feature films. Emerging in the late 1970s as one of the leading figures in the Neo-Expressionist movement, Schnabel’s works represent a break with the conceptual tradition that had afflicted American art in the previous decades. In a return to figuration, Schnabel crowds his canvas with heavy gestural brush strokes, paint drips, found materials – most famously broken plates – and substances such as wax, in a collage-like layering process on the various materials that function as his canvases. Schnabel’s themes are as wide ranging as his materials. Sexuality, identity, suffering, redemption and death are all aimed at engulfing the emotional state of the viewer. The typically enormous scale of a Schnabel work is also an important component of its power, as aggressively confrontational as his public persona. Often including words and text in his works, Schnabel has stated that he embraces ‘the subjectivity of the written word and the many forms it can take, and the many different meanings that are possible to different viewers depending on where they are from.’ (Julian Schnabel in Conversation with Alex Gartenfield, Julian Schnabel Permanently Becoming and the Architecture of Seeing, Thames and Hudson, 2011, Pg. 43). Schnabel leaves it to the viewer to form connections and find meaning between his images and text. In this sense, his collages work in a similar way as the ‘Combine’ paintings produced by Robert Rauschenberg in the mid-late 1950s: Rauschenberg’s conglomerations jostle newspaper clippings, paint and other found objects in a ramshackle assembly, each element vying for our interpretation. However, while Rauschenberg’s works were produced in the spirit of anti-art and absurdity, Schnabel’s are very much a celebration of art and the process of creation. The present lot began with a digitally printed image of a Japanese woodblock print of a courtesan; the figure is masked behind dripping layers of oil, wax and resin, weathered, attacked, even submerged in these accretions. The meaningless yet somehow allusive word ‘sonanbul’ – perhaps a misremembering of the French somnambule, sleepwalker – glides at a gentle diagonal above her head, hinting at significance without offering coherent meaning: there is an oblique yet eloquent dialogue between residue and underlying structure, the print’s original decorative frame made poignant and ruined. Schnabel’s exaggerated, chaotic surfaces are as loaded with emotion as with materials, but they are not heroic in the sense of history painting; they signal a change in attitude that emphasizes the emotion of expression. In 1986, Schnabel talked of the rejection of Conceptualism and Minimalism through a return to painting and figuration by artists in the late 1970s and 1980s as a seismic change. ‘There has been a shift in the emphasis of art. A break with the American tradition of painting. That break will define the end of this century. It is an essential break with the role of the heroic. A break with art’s need to be American or European.’ (Julian Schnabel in Conversation with Alex Gartenfield, Julian Schnabel Permanently Becoming and the Architecture of Seeing, Thames and Hudson, 2011, p.24). As Mick Brown writes, this was not an easy stance for Schnabel to take. ‘Critics vilified him as a huckster who personified the bloated, mercantile avarice of the age. Robert Hughes was par

.jpg)

Try LotSearch and its premium features for 7 days - without any costs!

Be notified automatically about new items in upcoming auctions.

Create an alert