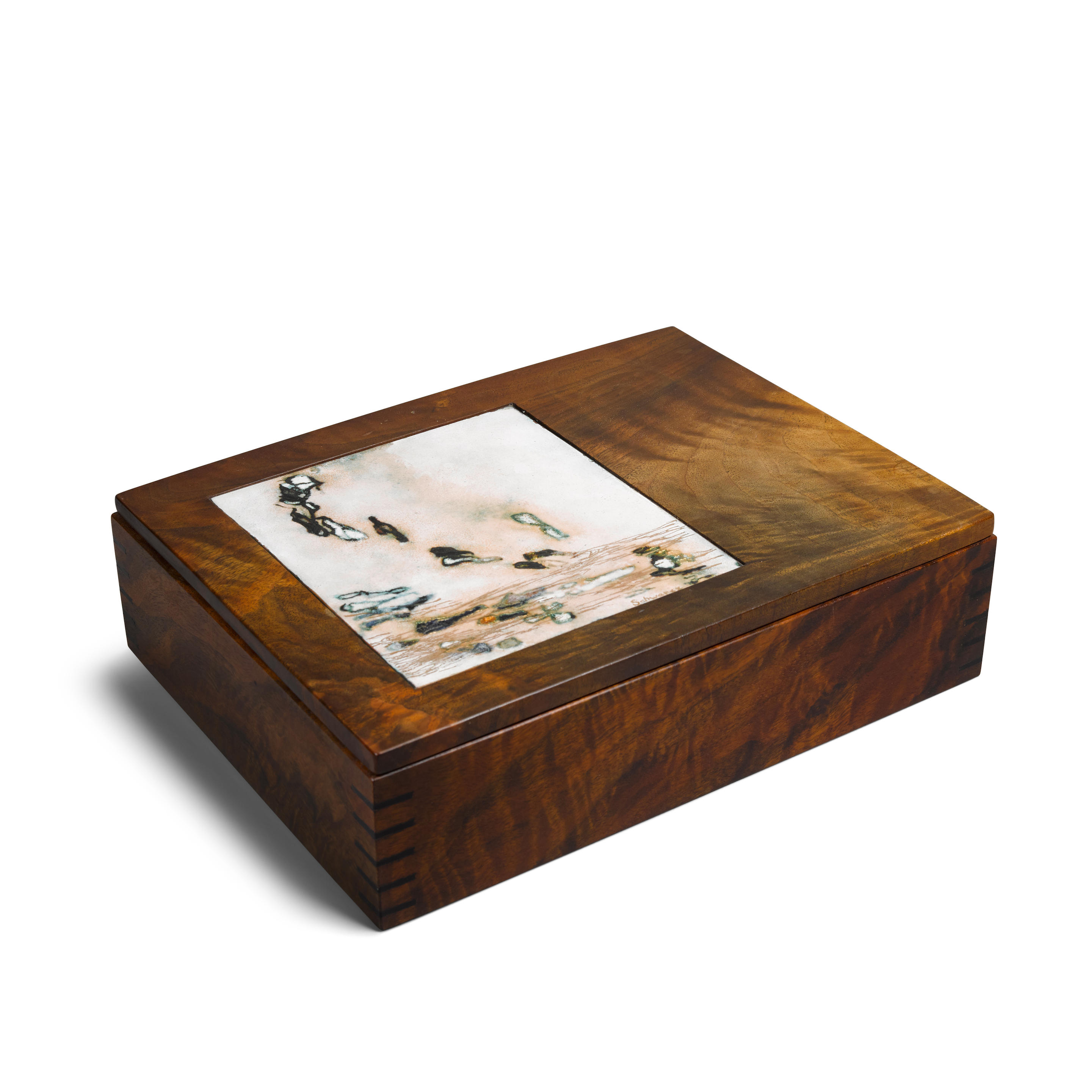

Property from the Collection of William Harper June Schwarcz Bowl #592 1971 Hammered copper with enamel, patina, and electroplated texture. 8 1/4 in. (21 cm) diameter

Provenance Acquired directly from the artist Literature Lee Nordness, Objects: USA, New York, 1970, p. 34 for a similar example June Schwarcz, Forty Years/Forty Pieces, exh. cat., San Francisco Craft & Folk Art Museum, 1998, p. 27 for a similar example Janet Koplos and Bruce Metcalf Makers: A History of American Studio Craft, Asheville, 2010, p. 341 for a similar example Catalogue Essay The tradition of hand-making objects has endured every industrial revolution and technological innovation and emerged all the better for it, with each new generation of maker armed with new material explorations and challenges to push traditional crafts into a contemporary context. In the 1960s and 1970s, the small corner of the design community that enamel occupied was undergoing a renaissance driven by two major figures who were trailblazing ahead with a new approach to an old art. Enamel is an ancient method of fusing crushed and ground glass into a smooth liquid that is applied to a metal surface in a decorative pattern, and it has been used by nearly every civilization from ancient times to the present. It requires enormous skill, patience and rigorous attention to detail, and for artists of the mid-twenieth century, it presented an opportunity to stop using enamel as a medium to mimic painting, but to admire it for what it is, and let it be its own materiality, fully recognized for its own singular and unique properties. Two of the biggest forces in this movement are June Schwarcz and William Harper whose work is shown and offered here in lots 93 and 94. June Schwarcz studied design at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York and began working with enamel in 1954 after happening upon an enamel workshop at the Denver Art Museum. Just two years later, her work was included in the inaugural exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Arts and Design) in New York, which immediately earned her recognition. By 1962, Schwarcz had moved to Sausalito, California and was exhibiting her work extensively. She began using sophisticated electroplating and electroforming techniques for a more sculptural effect in her vessels and became a pioneer of experimentation in this field. During this time, William Harper an enamelist from Cleveland, Ohio was on his first trip to New York City in 1966, and he visited the Museum of Contemporary Crafts where he saw Schwarcz’s work “using enamel in a way that [he] had never seen before.” Harper recalled in a 2004 interview for the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art that “seeing her work enforced that kind of undiscipline…in myself.” By 1970, Harper had been experimenting with welding techniques to achieve the “rough elegance” of Schwarcz’s work, which fortuitously led him to his own explorations of cloisonné, the ancient technique of using a thin wire to create a design to hold the enameled surface of an object, but Harper took a more freeform and sculptural approach, and this would be the technique that would become so emblematic of his work. By the late 1970s, Harper had the rare honor of a solo exhibition at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC and from that point on would be represented by some of the most prominent galleries of the movement including Helen Drutt, the Kennedy Galleries, Peter Joseph and Franklin Parrasch. In 1998, on the occasion of a retrospective of June Schwarcz’s life work in the field of enamel at the San Francisco Craft and Folk Art Museum, William Harper was tapped to interview Schwarcz for the museum’s exhibition catalogue. In the long-standing tradition of artist relationships, the two artists traded works for each to have in their own personal collections. The June Schwarcz bowl, shown here in lot 93, was traded that day for the William Harper brooch, lot 94. Reunited here in these pages, these works are the culmination of the careers of two artists who pushed America into the spotlight for their experimentation in the field

Property from the Collection of William Harper June Schwarcz Bowl #592 1971 Hammered copper with enamel, patina, and electroplated texture. 8 1/4 in. (21 cm) diameter

Provenance Acquired directly from the artist Literature Lee Nordness, Objects: USA, New York, 1970, p. 34 for a similar example June Schwarcz, Forty Years/Forty Pieces, exh. cat., San Francisco Craft & Folk Art Museum, 1998, p. 27 for a similar example Janet Koplos and Bruce Metcalf Makers: A History of American Studio Craft, Asheville, 2010, p. 341 for a similar example Catalogue Essay The tradition of hand-making objects has endured every industrial revolution and technological innovation and emerged all the better for it, with each new generation of maker armed with new material explorations and challenges to push traditional crafts into a contemporary context. In the 1960s and 1970s, the small corner of the design community that enamel occupied was undergoing a renaissance driven by two major figures who were trailblazing ahead with a new approach to an old art. Enamel is an ancient method of fusing crushed and ground glass into a smooth liquid that is applied to a metal surface in a decorative pattern, and it has been used by nearly every civilization from ancient times to the present. It requires enormous skill, patience and rigorous attention to detail, and for artists of the mid-twenieth century, it presented an opportunity to stop using enamel as a medium to mimic painting, but to admire it for what it is, and let it be its own materiality, fully recognized for its own singular and unique properties. Two of the biggest forces in this movement are June Schwarcz and William Harper whose work is shown and offered here in lots 93 and 94. June Schwarcz studied design at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York and began working with enamel in 1954 after happening upon an enamel workshop at the Denver Art Museum. Just two years later, her work was included in the inaugural exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Arts and Design) in New York, which immediately earned her recognition. By 1962, Schwarcz had moved to Sausalito, California and was exhibiting her work extensively. She began using sophisticated electroplating and electroforming techniques for a more sculptural effect in her vessels and became a pioneer of experimentation in this field. During this time, William Harper an enamelist from Cleveland, Ohio was on his first trip to New York City in 1966, and he visited the Museum of Contemporary Crafts where he saw Schwarcz’s work “using enamel in a way that [he] had never seen before.” Harper recalled in a 2004 interview for the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art that “seeing her work enforced that kind of undiscipline…in myself.” By 1970, Harper had been experimenting with welding techniques to achieve the “rough elegance” of Schwarcz’s work, which fortuitously led him to his own explorations of cloisonné, the ancient technique of using a thin wire to create a design to hold the enameled surface of an object, but Harper took a more freeform and sculptural approach, and this would be the technique that would become so emblematic of his work. By the late 1970s, Harper had the rare honor of a solo exhibition at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC and from that point on would be represented by some of the most prominent galleries of the movement including Helen Drutt, the Kennedy Galleries, Peter Joseph and Franklin Parrasch. In 1998, on the occasion of a retrospective of June Schwarcz’s life work in the field of enamel at the San Francisco Craft and Folk Art Museum, William Harper was tapped to interview Schwarcz for the museum’s exhibition catalogue. In the long-standing tradition of artist relationships, the two artists traded works for each to have in their own personal collections. The June Schwarcz bowl, shown here in lot 93, was traded that day for the William Harper brooch, lot 94. Reunited here in these pages, these works are the culmination of the careers of two artists who pushed America into the spotlight for their experimentation in the field

Try LotSearch and its premium features for 7 days - without any costs!

Be notified automatically about new items in upcoming auctions.

Create an alert