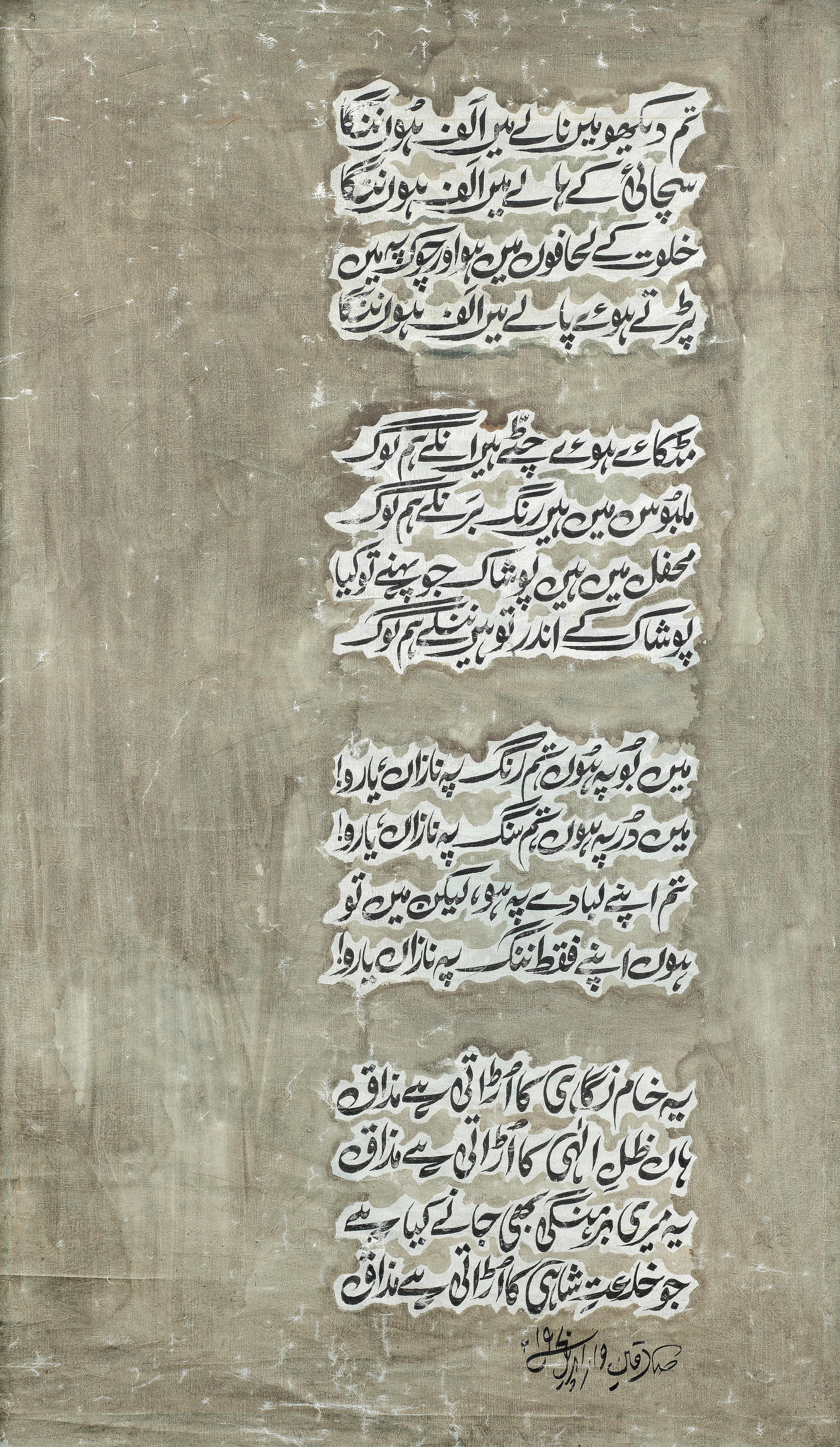

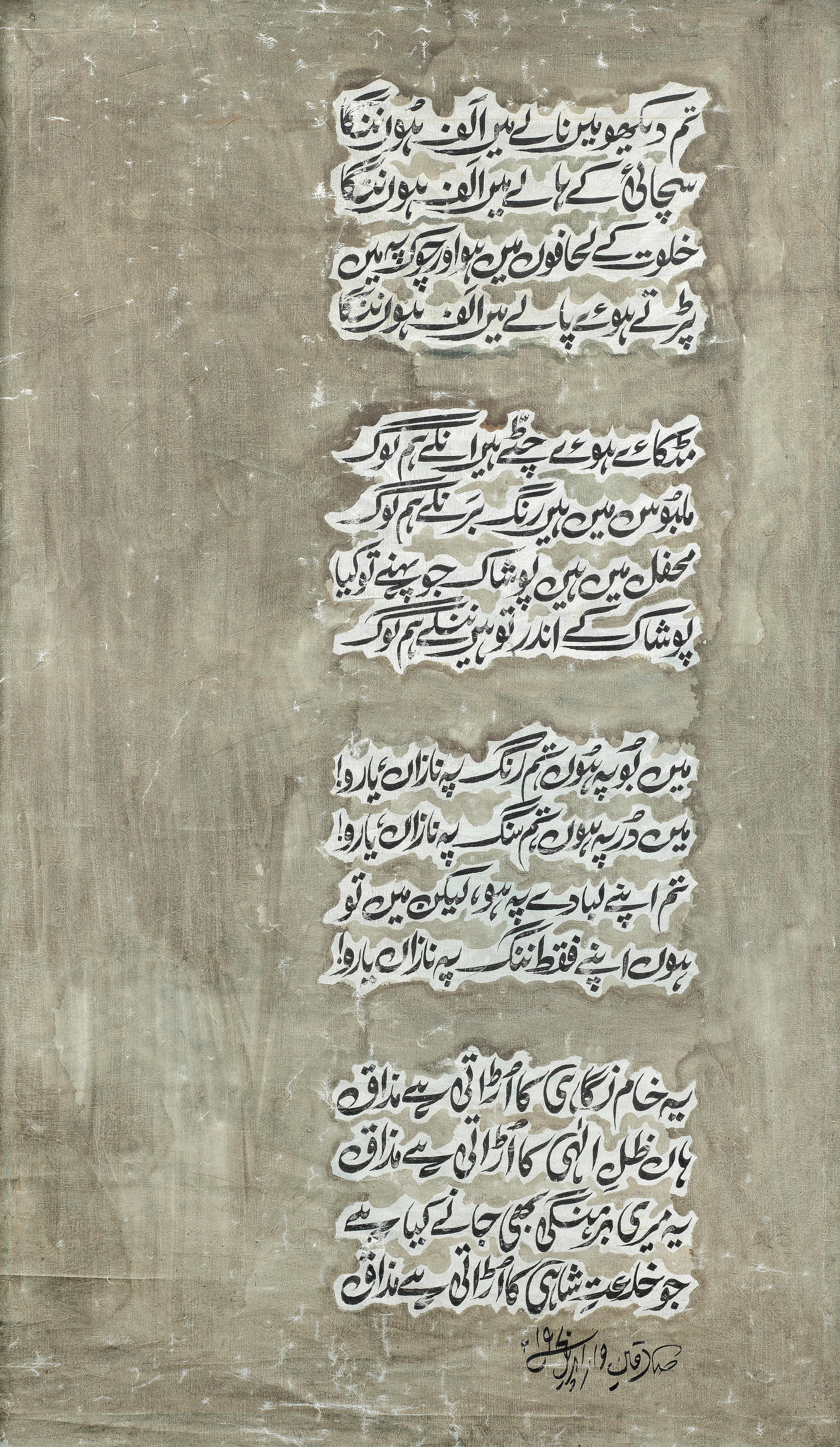

Sadequain (1930-1987)Surah Ya-Sin

circa 1970s

markers on mylar

56 x 1945cm (22 1/16 x 765 3/4in).FootnotesProvenance

Property from a private collection, Illinoi, USA.

Acquired from Mrs Ali Imam, wife of Mr Imam, owner of Indus Gallery Karachi.

Translation:

بِسۡمِ ٱللَّهِ ٱلرَّحۡمَٰنِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ

Bismillahir-Rahmanir-Rahim.

In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful

يسٓ

Yasin!

Allah alone knows the meaning of this.

وَٱلۡقُرۡءَانِ ٱلۡحَكِيمِ

Wal-Qur'anil-Vakim

By the florious Qur'an of supreme widsom.

إِنَّكَ لَمِنَ ٱلۡمُرۡسَلِينَ

Innaka laminal mursaleen

Surely you (Muhammad) are of the sent-ones.

عَلَىٰ صِرَٰطٖ مُّسۡتَقِيمٖ

Alaa Siraatim Mustaqeem

On a straight path.

تَنزِيلَ ٱلۡعَزِيزِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ

Tanzeelal 'Azeezir Raheem

(This Qur'an is) sent down by the Almighty, the Merciful.

لِتُنذِرَ قَوۡمٗا مَّآ أُنذِرَ ءَابَآؤُهُمۡ فَهُمۡ غَٰفِلُونَ

Litunzira qawmam maaa unzira aabaaa'uhum fahum ghaafiloon

That you may warn a nation whose forefathers were not warned (for long), so they are also unaware.

لَقَدۡ حَقَّ ٱلۡقَوۡلُ عَلَىٰٓ أَكۡثَرِهِمۡ فَهُمۡ لَا يُؤۡمِنُونَ

Laqad haqqal qawlu 'alaaa aksarihim fahum laa yu'minoon

Surely (because of their persistent disbelief and hatred) the word (decree) has been proved against most of them that they will not believe.

إِنَّا جَعَلۡنَا فِيٓ أَعۡنَٰقِهِمۡ أَغۡلَٰلٗا فَهِيَ إِلَى ٱلۡأَذۡقَانِ فَهُم مُّقۡمَحُونَ

Innaa ja'alnaa feee a'naaqihim aghlaalan fahiya ilal azqaani fahum muqmahoon

Surely we have placed on their necks shackles reaching right up to their chins so that their heads are raised up.

وَجَعَلۡنَا مِنۢ بَيۡنِ أَيۡدِيهِمۡ سَدّٗا وَمِنۡ خَلۡفِهِمۡ سَدّٗا فَأَغۡشَيۡنَٰهُمۡ فَهُمۡ لَا يُبۡصِرُونَ

Wa ja'alnaa mim baini aydeehim saddanw-wa min khalfihim saddan fa aghshai naahum fahum laa yubsiroon

And we have set a barrier before them and a barrier behind them and case a veil over their eyes, so they see nothing.

وَسَوَآءٌ عَلَيۡهِمۡ ءَأَنذَرۡتَهُمۡ أَمۡ لَمۡ تُنذِرۡهُمۡ لَا يُؤۡمِنُونَ

Wa sawaaa'un 'alaihim 'a-anzartahum am lam tunzirhum laa yu'minoon

And it is all the same for them whether you warn them or do not warn them – they will not believe.

إِنَّمَا تُنذِرُ مَنِ ٱتَّبَعَ ٱلذِّكۡرَ وَخَشِيَ ٱلرَّحۡمَٰنَ بِٱلۡغَيۡبِۖ فَبَشِّرۡهُ بِمَغۡفِرَةٖ وَأَجۡرٖ كَرِيمٍ

Innamaa tunziru manit taba 'az-Zikra wa khashiyar Rahmaana bilghaib, fabashshirhu bimaghfiratinw-wa ajrin kareem

You can only warn one who follows the message and fears the Most Merciful unseen. So give him good tidings of forgiveness and noble reward.

إِنَّا نَحۡنُ نُحۡيِ ٱلۡمَوۡتَىٰ وَنَكۡتُبُ مَا قَدَّمُواْ وَءَاثَٰرَهُمۡۚ وَكُلَّ شَيۡءٍ أَحۡصَيۡنَٰهُ فِيٓ إِمَامٖ مُّبِينٖ

Innaa Nahnu nuhyil mawtaa wa naktubu maa qaddamoo wa aasaarahum; wa kulla shai'in ahsainaahu feee Imaamim Mubeen

Indeed, it is We who bring the dead to life and record what they have put forth and what they left behind, and all things We have enumerated in a clear register.

وَٱضۡرِبۡ لَهُم مَّثَلًا أَصۡحَٰبَ ٱلۡقَرۡيَةِ إِذۡ جَآءَهَا ٱلۡمُرۡسَلُونَ

Wadrib lahum masalan Ashaabal Qaryatih; iz jaaa'ahal mursaloon

And present to them an example: the people of the city, when the messengers came to it –

إِذۡ أَرۡسَلۡنَآ إِلَيۡهِمُ ٱثۡنَيۡنِ فَكَذَّبُوهُمَا فَعَزَّزۡنَا بِثَالِثٖ فَقَالُوٓاْ إِنَّآ إِلَيۡكُم مُّرۡسَلُونَ

Iz arsalnaaa ilaihimusnaini fakazzaboohumaa fa'azzaznaa bisaalisin faqaalooo innaaa ilaikum mursaloon

When We sent to them two but they denied them, so We strengthened them with a third, and they said, "Indeed, we are messengers to you."

قَالُواْ مَآ أَنتُمۡ إِلَّا بَشَرٞ مِّثۡلُنَا وَمَآ أَنزَلَ ٱلرَّحۡمَٰنُ مِن شَيۡءٍ إِنۡ أَنتُمۡ إِلَّ تَكۡذِبُونَ

Qaaloo maaa antum illaa basharum mislunaa wa maaa anzalar Rahmaanu min shai'in in antum illaa takziboon

They said, "You are not but human beings like us, and the Most Merciful has not revealed a thing. You are only telling lies."

قَالُواْ رَبُّنَا يَعۡلَمُ إِنَّآ إِلَيۡكُمۡ لَمُرۡسَلُونَ

Qaaloo Rabbunaa ya'lamu innaaa ilaikum lamursaloon

They said, "Our Lord knows that we are messengers to you,

وَمَا عَلَيۡنَآ إِلَّا ٱلۡبَلَٰغُ ٱلۡمُبِينُ

Wa maa 'alainaaa illal balaaghul mubeen

And we are not responsible except for clear notification."

قَالُوٓاْ إِنَّا تَطَيَّرۡنَا بِكُمۡۖ لَئِن لَّمۡ تَنتَهُواْ لَنَرۡجُمَنَّكُمۡ وَلَيَمَسَّنَّكُم مِّنَّا عَذَابٌ أَلِيمٞ

Qaaloo innaa tataiyarnaa bikum la'il-lam tantahoo lanar jumannakum wa la-yamassan nakum minnaa 'azaabun aleem

They said, "Indeed, we consider you a bad omen. If you do not desist, we will surely stone you, and there will surely touch you, from us, a painful punishment."

قَالُواْ طَـٰٓئِرُكُم مَّعَكُمۡ أَئِن ذُكِّرۡتُمۚ بَلۡ أَنتُمۡ قَوۡمٞ مُّسۡرِفُونَ

Qaaloo taaa'irukum ma'akum; a'in zukkirtum; bal antum qawmum musrifoon

They said, "Your omen is with yourselves. Is it because you were reminded? Rather, you are a transgressing people."

وَجَآءَ مِنۡ أَقۡصَا ٱلۡمَدِينَةِ رَجُلٞ يَسۡعَىٰ قَالَ يَٰقَوۡمِ ٱتَّبِعُواْ ٱلۡمُرۡسَلِينَ

Wa jaaa'a min aqsal madeenati rajuluny yas'aa qaala yaa qawmit tabi'ul mursaleen

And there came from the farthest end of the city a man, running. He said, "O my people, follow the messengers.

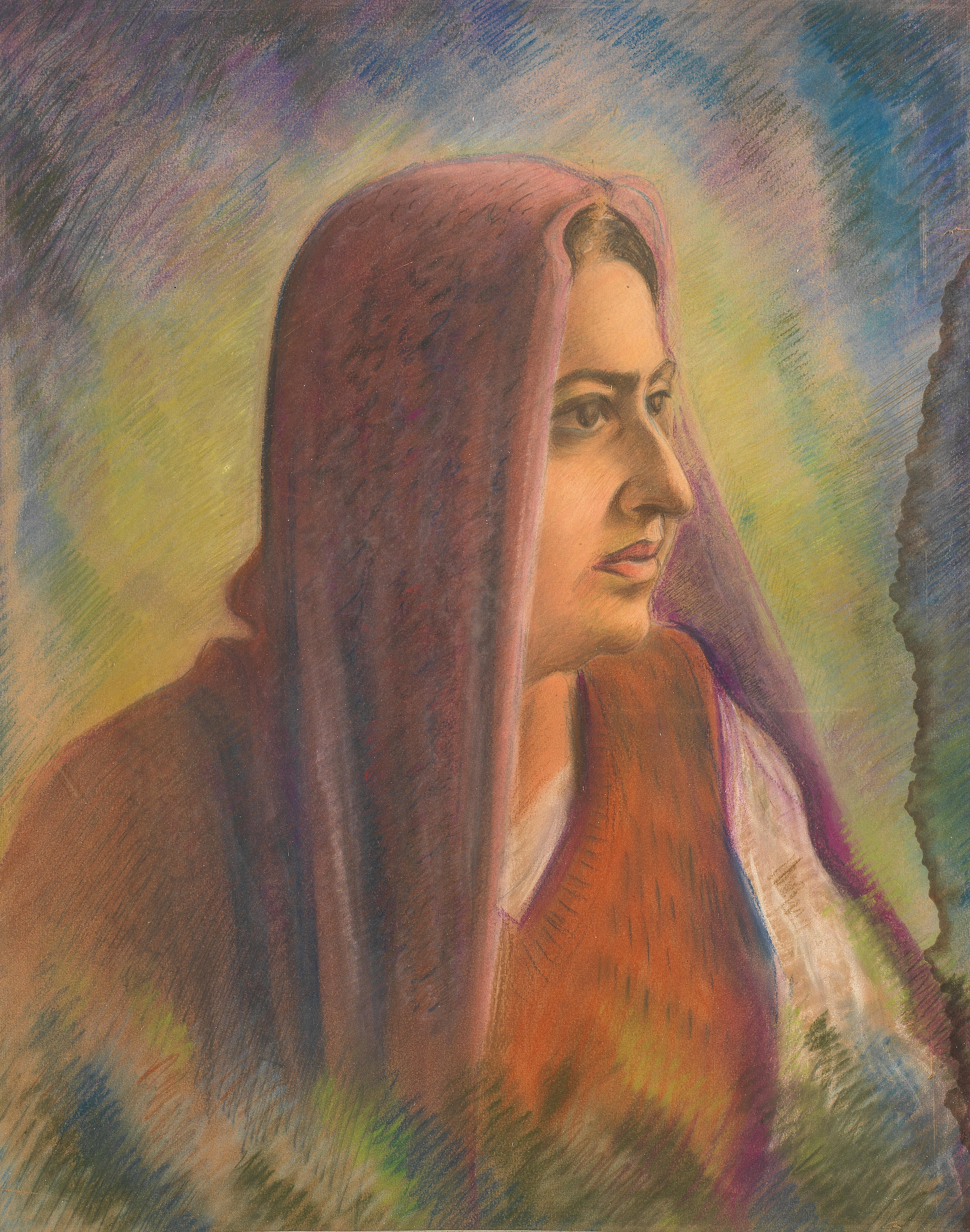

Sadequain - The Faqir by Salima Hashmi

Sadequain (1930-1987) caught the imagination of the Pakistani public like no other painter of his time and validated the notion of a Bohemian searching for enlightenment. Born in 1930 in Amroha, India, into an educated, cultured family where both poetry and khushkhati (calligraphy) were an intrinsic part of daily life, Sadequain's talent for both was evident from an early age. His flair for poetry, specifically the rubaiyat (quatrain) form, was honed by his job as a calligrapher/copyist in All India Radio in 1944 where he copied classical poetry as well as the contemporary work of poets like Akhter Shirani and Josh Malihabadi. He taught drawing in Amroha in 1946 before he graduated from Agra University in 1948.

Sadequain was spared the traumatic exodus of millions of others from across the border by moving to Karachi a year after Partition. But he lamented later that most of his poetry and art works were left behind, the paintings that had adorned his school, 'Imam ul Madaras', in Amroha never seen again. Little is known of much of his work preceding 1955.

He continued working as a copyist in Radio Pakistan alongside his art practice, and had his first solo exhibition in 1954 in Quetta. The following year he exhibited a number of his works at the residence of the Prime Minister Huseyn Shaheed Suharwardy, a patron of the arts. Major public commissions like the PIA airport terminal in Karachi followed. He was also commissioned for a mural at the Jinnah Hospital, Karachi, where coincidentally he was admitted for treatment for his ill health. He set up a studio in an ante-room in the hospital and set to work.

Wandering further inland to Gadani in Balochistan with friends, the artist chanced upon the local vegetation—giant cacti. Their linear, thorny shapes embodied a harshness and resilience in nature that he found compelling and they became a recurring symbol in his drawings and paintings. Perhaps it was also significant that the cacti paralleled calligraphic forms, in particular the first letter of the alphabet, alif: vertical, imposing and forceful. Sensing the correspondence between these towering plant forms and the human body, Sadequain set up a studio amid the cacti in 1958. His art began to reflect the tortuous shapes of the cacti—fingers, hair, body, even inanimate objects, metamorphosed into these thorn-like entanglements.

Sadequain went to Paris for the first time in 1960 on the invitation of the French Committee of the International Association of Plastic Arts. He was already well on his way to becoming recognised as a prominent artist in Pakistan, but Paris was where his international outreach began and he was often compared to Picasso. Certainly, Picasso's influence was evident in Sadequain's use of line circumscribing the human form. He won the Paris Laureate award (for under 35s) in 1961 which ensured the means to travel across Europe, the USA and Britain. He returned to the cactus in the desert again and again, even when he lay in his hospital bed in Paris in 1962—he reinterpreted the cityscape visible through his window as interlocking calligraphic cacti spread across the horizon.

Sadequain's drawings were in the process of developing his individual content steeped in literary and formal conventions, including the calligraphic mark-making inherent in his work. In Paris he also acquainted himself with print-making techniques. The commission to illustrate Albert Camus's L'Étranger in France reinforced his reputation as an artist of substance, his thoughtful lithographic illustrations remain a testament to his capabilities. Not many images of Sadequain's paintings from Paris are on record—possibly due to his proclivity for gifting his work—but the 'City by Night' series displays his love for dark and dramatic themes, depicting gloomy buildings rendered by calligraphic brush marks set against a deep indigo sky.

His féted return to Pakistan in 1967 brought commissions and constant exhibitions, the setting up of his own gallery in Karachi and events where he could present his work. The pace was formidable; paintings completed every day to dazzle onlookers, admirers and friends. The series on the poet Ghalib in 1968 was a critical triumph and was indicative of the artist's ability to explore new imagery—a maturing of his calligraphic forms and his relationship to the human body. Sadequain placed Ghalib in his own social and political context, vastly different to Chughtai's celebrated Muraqqa-e-Chughtai on the same subject. Highly romantic in style, Chughtai's imagery was lyrical, literal and ornamental, Sadequain's dramatic, forceful and interpretive.

It was no coincidence that Sadequain was aware of the stature a poet claimed in the public imagination. A calligraphed edition of his own poetry accompanied by drawings appeared in 1970 underscoring his autobiographical leanings. Yet it is for his prodigious artistic output that Sadequain is remembered, the punishing intensity never better reflected than in his Sar-ba-Kaf series. Sadequain was by now assembling a vocabulary which was filtered into highly charged self-image. The separation of his head from his body is a reference to the Sufi mystic Sarmad, decapitated for being an apostate. The artist was equating himself to a Sufi malamati or penitent—the faqir who abjures the accepted laws of society to make his own connection with God.

By the 1970s, Sadequain had determinedly moved centre stage in the public eye as a charismatic symbol of national artistic excellence. His utilisation of calligraphy as a potent component of his art was established, and his work—from Iqbal's verses to the Quran—was immediately recognisable and celebrated. The monumental panel with the Surah e Yaseen is from Sadeqains creative phase where he consciously adapted the Arabic calligraphy placed against a vigorous series of patterns which owed more to Subcontinental traditions of embellishment rather than the traditional illuminated Quranic manuscript. The Surah describes the importance of the Word itself which guides the non believers and brings them to the righteous path. He moved away from the tutored forms of calligraphies to a more innovative redesigning of the letters, adding radical new structures and flourishes which became identified with his name but often obscured his other strengths and proclivities.

In the 1980s, during the military regime of General Zia-ul-Haq, Quranic calligraphy was afforded state patronage over other forms of art. A certain pliancy was essential if artists were to survive. Sadequain was courted for his undisputed status as a master calligrapher distinct from those who followed the more conservative tenets of Islamic calligraphy, his dynamic active patterns derived from sources other than the traditional Quran manuscript page. His Quranic verses were rendered on an assortment of surfaces, ranging from leather to tracing paper to wood, and in an equally assorted number of mediums.

The unmistakable stamp of Sadequain's energy could never be confused with regular calligraphic masters, though his later works of the 1980s commissioned by both private and public patrons became repetitive, forgoing the freshness of the earlier phase of his calligraphy. But the sheer volume of Sadequain's body of work and his ever-growing popularity cement his place among the most significant artists of his era.

Bonhams extends their gratitude to Mrs Salima Hashmi for her assistance with cataloguing this work.

Sadequain (1930-1987)Surah Ya-Sin

circa 1970s

markers on mylar

56 x 1945cm (22 1/16 x 765 3/4in).FootnotesProvenance

Property from a private collection, Illinoi, USA.

Acquired from Mrs Ali Imam, wife of Mr Imam, owner of Indus Gallery Karachi.

Translation:

بِسۡمِ ٱللَّهِ ٱلرَّحۡمَٰنِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ

Bismillahir-Rahmanir-Rahim.

In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful

يسٓ

Yasin!

Allah alone knows the meaning of this.

وَٱلۡقُرۡءَانِ ٱلۡحَكِيمِ

Wal-Qur'anil-Vakim

By the florious Qur'an of supreme widsom.

إِنَّكَ لَمِنَ ٱلۡمُرۡسَلِينَ

Innaka laminal mursaleen

Surely you (Muhammad) are of the sent-ones.

عَلَىٰ صِرَٰطٖ مُّسۡتَقِيمٖ

Alaa Siraatim Mustaqeem

On a straight path.

تَنزِيلَ ٱلۡعَزِيزِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ

Tanzeelal 'Azeezir Raheem

(This Qur'an is) sent down by the Almighty, the Merciful.

لِتُنذِرَ قَوۡمٗا مَّآ أُنذِرَ ءَابَآؤُهُمۡ فَهُمۡ غَٰفِلُونَ

Litunzira qawmam maaa unzira aabaaa'uhum fahum ghaafiloon

That you may warn a nation whose forefathers were not warned (for long), so they are also unaware.

لَقَدۡ حَقَّ ٱلۡقَوۡلُ عَلَىٰٓ أَكۡثَرِهِمۡ فَهُمۡ لَا يُؤۡمِنُونَ

Laqad haqqal qawlu 'alaaa aksarihim fahum laa yu'minoon

Surely (because of their persistent disbelief and hatred) the word (decree) has been proved against most of them that they will not believe.

إِنَّا جَعَلۡنَا فِيٓ أَعۡنَٰقِهِمۡ أَغۡلَٰلٗا فَهِيَ إِلَى ٱلۡأَذۡقَانِ فَهُم مُّقۡمَحُونَ

Innaa ja'alnaa feee a'naaqihim aghlaalan fahiya ilal azqaani fahum muqmahoon

Surely we have placed on their necks shackles reaching right up to their chins so that their heads are raised up.

وَجَعَلۡنَا مِنۢ بَيۡنِ أَيۡدِيهِمۡ سَدّٗا وَمِنۡ خَلۡفِهِمۡ سَدّٗا فَأَغۡشَيۡنَٰهُمۡ فَهُمۡ لَا يُبۡصِرُونَ

Wa ja'alnaa mim baini aydeehim saddanw-wa min khalfihim saddan fa aghshai naahum fahum laa yubsiroon

And we have set a barrier before them and a barrier behind them and case a veil over their eyes, so they see nothing.

وَسَوَآءٌ عَلَيۡهِمۡ ءَأَنذَرۡتَهُمۡ أَمۡ لَمۡ تُنذِرۡهُمۡ لَا يُؤۡمِنُونَ

Wa sawaaa'un 'alaihim 'a-anzartahum am lam tunzirhum laa yu'minoon

And it is all the same for them whether you warn them or do not warn them – they will not believe.

إِنَّمَا تُنذِرُ مَنِ ٱتَّبَعَ ٱلذِّكۡرَ وَخَشِيَ ٱلرَّحۡمَٰنَ بِٱلۡغَيۡبِۖ فَبَشِّرۡهُ بِمَغۡفِرَةٖ وَأَجۡرٖ كَرِيمٍ

Innamaa tunziru manit taba 'az-Zikra wa khashiyar Rahmaana bilghaib, fabashshirhu bimaghfiratinw-wa ajrin kareem

You can only warn one who follows the message and fears the Most Merciful unseen. So give him good tidings of forgiveness and noble reward.

إِنَّا نَحۡنُ نُحۡيِ ٱلۡمَوۡتَىٰ وَنَكۡتُبُ مَا قَدَّمُواْ وَءَاثَٰرَهُمۡۚ وَكُلَّ شَيۡءٍ أَحۡصَيۡنَٰهُ فِيٓ إِمَامٖ مُّبِينٖ

Innaa Nahnu nuhyil mawtaa wa naktubu maa qaddamoo wa aasaarahum; wa kulla shai'in ahsainaahu feee Imaamim Mubeen

Indeed, it is We who bring the dead to life and record what they have put forth and what they left behind, and all things We have enumerated in a clear register.

وَٱضۡرِبۡ لَهُم مَّثَلًا أَصۡحَٰبَ ٱلۡقَرۡيَةِ إِذۡ جَآءَهَا ٱلۡمُرۡسَلُونَ

Wadrib lahum masalan Ashaabal Qaryatih; iz jaaa'ahal mursaloon

And present to them an example: the people of the city, when the messengers came to it –

إِذۡ أَرۡسَلۡنَآ إِلَيۡهِمُ ٱثۡنَيۡنِ فَكَذَّبُوهُمَا فَعَزَّزۡنَا بِثَالِثٖ فَقَالُوٓاْ إِنَّآ إِلَيۡكُم مُّرۡسَلُونَ

Iz arsalnaaa ilaihimusnaini fakazzaboohumaa fa'azzaznaa bisaalisin faqaalooo innaaa ilaikum mursaloon

When We sent to them two but they denied them, so We strengthened them with a third, and they said, "Indeed, we are messengers to you."

قَالُواْ مَآ أَنتُمۡ إِلَّا بَشَرٞ مِّثۡلُنَا وَمَآ أَنزَلَ ٱلرَّحۡمَٰنُ مِن شَيۡءٍ إِنۡ أَنتُمۡ إِلَّ تَكۡذِبُونَ

Qaaloo maaa antum illaa basharum mislunaa wa maaa anzalar Rahmaanu min shai'in in antum illaa takziboon

They said, "You are not but human beings like us, and the Most Merciful has not revealed a thing. You are only telling lies."

قَالُواْ رَبُّنَا يَعۡلَمُ إِنَّآ إِلَيۡكُمۡ لَمُرۡسَلُونَ

Qaaloo Rabbunaa ya'lamu innaaa ilaikum lamursaloon

They said, "Our Lord knows that we are messengers to you,

وَمَا عَلَيۡنَآ إِلَّا ٱلۡبَلَٰغُ ٱلۡمُبِينُ

Wa maa 'alainaaa illal balaaghul mubeen

And we are not responsible except for clear notification."

قَالُوٓاْ إِنَّا تَطَيَّرۡنَا بِكُمۡۖ لَئِن لَّمۡ تَنتَهُواْ لَنَرۡجُمَنَّكُمۡ وَلَيَمَسَّنَّكُم مِّنَّا عَذَابٌ أَلِيمٞ

Qaaloo innaa tataiyarnaa bikum la'il-lam tantahoo lanar jumannakum wa la-yamassan nakum minnaa 'azaabun aleem

They said, "Indeed, we consider you a bad omen. If you do not desist, we will surely stone you, and there will surely touch you, from us, a painful punishment."

قَالُواْ طَـٰٓئِرُكُم مَّعَكُمۡ أَئِن ذُكِّرۡتُمۚ بَلۡ أَنتُمۡ قَوۡمٞ مُّسۡرِفُونَ

Qaaloo taaa'irukum ma'akum; a'in zukkirtum; bal antum qawmum musrifoon

They said, "Your omen is with yourselves. Is it because you were reminded? Rather, you are a transgressing people."

وَجَآءَ مِنۡ أَقۡصَا ٱلۡمَدِينَةِ رَجُلٞ يَسۡعَىٰ قَالَ يَٰقَوۡمِ ٱتَّبِعُواْ ٱلۡمُرۡسَلِينَ

Wa jaaa'a min aqsal madeenati rajuluny yas'aa qaala yaa qawmit tabi'ul mursaleen

And there came from the farthest end of the city a man, running. He said, "O my people, follow the messengers.

Sadequain - The Faqir by Salima Hashmi

Sadequain (1930-1987) caught the imagination of the Pakistani public like no other painter of his time and validated the notion of a Bohemian searching for enlightenment. Born in 1930 in Amroha, India, into an educated, cultured family where both poetry and khushkhati (calligraphy) were an intrinsic part of daily life, Sadequain's talent for both was evident from an early age. His flair for poetry, specifically the rubaiyat (quatrain) form, was honed by his job as a calligrapher/copyist in All India Radio in 1944 where he copied classical poetry as well as the contemporary work of poets like Akhter Shirani and Josh Malihabadi. He taught drawing in Amroha in 1946 before he graduated from Agra University in 1948.

Sadequain was spared the traumatic exodus of millions of others from across the border by moving to Karachi a year after Partition. But he lamented later that most of his poetry and art works were left behind, the paintings that had adorned his school, 'Imam ul Madaras', in Amroha never seen again. Little is known of much of his work preceding 1955.

He continued working as a copyist in Radio Pakistan alongside his art practice, and had his first solo exhibition in 1954 in Quetta. The following year he exhibited a number of his works at the residence of the Prime Minister Huseyn Shaheed Suharwardy, a patron of the arts. Major public commissions like the PIA airport terminal in Karachi followed. He was also commissioned for a mural at the Jinnah Hospital, Karachi, where coincidentally he was admitted for treatment for his ill health. He set up a studio in an ante-room in the hospital and set to work.

Wandering further inland to Gadani in Balochistan with friends, the artist chanced upon the local vegetation—giant cacti. Their linear, thorny shapes embodied a harshness and resilience in nature that he found compelling and they became a recurring symbol in his drawings and paintings. Perhaps it was also significant that the cacti paralleled calligraphic forms, in particular the first letter of the alphabet, alif: vertical, imposing and forceful. Sensing the correspondence between these towering plant forms and the human body, Sadequain set up a studio amid the cacti in 1958. His art began to reflect the tortuous shapes of the cacti—fingers, hair, body, even inanimate objects, metamorphosed into these thorn-like entanglements.

Sadequain went to Paris for the first time in 1960 on the invitation of the French Committee of the International Association of Plastic Arts. He was already well on his way to becoming recognised as a prominent artist in Pakistan, but Paris was where his international outreach began and he was often compared to Picasso. Certainly, Picasso's influence was evident in Sadequain's use of line circumscribing the human form. He won the Paris Laureate award (for under 35s) in 1961 which ensured the means to travel across Europe, the USA and Britain. He returned to the cactus in the desert again and again, even when he lay in his hospital bed in Paris in 1962—he reinterpreted the cityscape visible through his window as interlocking calligraphic cacti spread across the horizon.

Sadequain's drawings were in the process of developing his individual content steeped in literary and formal conventions, including the calligraphic mark-making inherent in his work. In Paris he also acquainted himself with print-making techniques. The commission to illustrate Albert Camus's L'Étranger in France reinforced his reputation as an artist of substance, his thoughtful lithographic illustrations remain a testament to his capabilities. Not many images of Sadequain's paintings from Paris are on record—possibly due to his proclivity for gifting his work—but the 'City by Night' series displays his love for dark and dramatic themes, depicting gloomy buildings rendered by calligraphic brush marks set against a deep indigo sky.

His féted return to Pakistan in 1967 brought commissions and constant exhibitions, the setting up of his own gallery in Karachi and events where he could present his work. The pace was formidable; paintings completed every day to dazzle onlookers, admirers and friends. The series on the poet Ghalib in 1968 was a critical triumph and was indicative of the artist's ability to explore new imagery—a maturing of his calligraphic forms and his relationship to the human body. Sadequain placed Ghalib in his own social and political context, vastly different to Chughtai's celebrated Muraqqa-e-Chughtai on the same subject. Highly romantic in style, Chughtai's imagery was lyrical, literal and ornamental, Sadequain's dramatic, forceful and interpretive.

It was no coincidence that Sadequain was aware of the stature a poet claimed in the public imagination. A calligraphed edition of his own poetry accompanied by drawings appeared in 1970 underscoring his autobiographical leanings. Yet it is for his prodigious artistic output that Sadequain is remembered, the punishing intensity never better reflected than in his Sar-ba-Kaf series. Sadequain was by now assembling a vocabulary which was filtered into highly charged self-image. The separation of his head from his body is a reference to the Sufi mystic Sarmad, decapitated for being an apostate. The artist was equating himself to a Sufi malamati or penitent—the faqir who abjures the accepted laws of society to make his own connection with God.

By the 1970s, Sadequain had determinedly moved centre stage in the public eye as a charismatic symbol of national artistic excellence. His utilisation of calligraphy as a potent component of his art was established, and his work—from Iqbal's verses to the Quran—was immediately recognisable and celebrated. The monumental panel with the Surah e Yaseen is from Sadeqains creative phase where he consciously adapted the Arabic calligraphy placed against a vigorous series of patterns which owed more to Subcontinental traditions of embellishment rather than the traditional illuminated Quranic manuscript. The Surah describes the importance of the Word itself which guides the non believers and brings them to the righteous path. He moved away from the tutored forms of calligraphies to a more innovative redesigning of the letters, adding radical new structures and flourishes which became identified with his name but often obscured his other strengths and proclivities.

In the 1980s, during the military regime of General Zia-ul-Haq, Quranic calligraphy was afforded state patronage over other forms of art. A certain pliancy was essential if artists were to survive. Sadequain was courted for his undisputed status as a master calligrapher distinct from those who followed the more conservative tenets of Islamic calligraphy, his dynamic active patterns derived from sources other than the traditional Quran manuscript page. His Quranic verses were rendered on an assortment of surfaces, ranging from leather to tracing paper to wood, and in an equally assorted number of mediums.

The unmistakable stamp of Sadequain's energy could never be confused with regular calligraphic masters, though his later works of the 1980s commissioned by both private and public patrons became repetitive, forgoing the freshness of the earlier phase of his calligraphy. But the sheer volume of Sadequain's body of work and his ever-growing popularity cement his place among the most significant artists of his era.

Bonhams extends their gratitude to Mrs Salima Hashmi for her assistance with cataloguing this work.

.jpg)

Try LotSearch and its premium features for 7 days - without any costs!

Be notified automatically about new items in upcoming auctions.

Create an alert