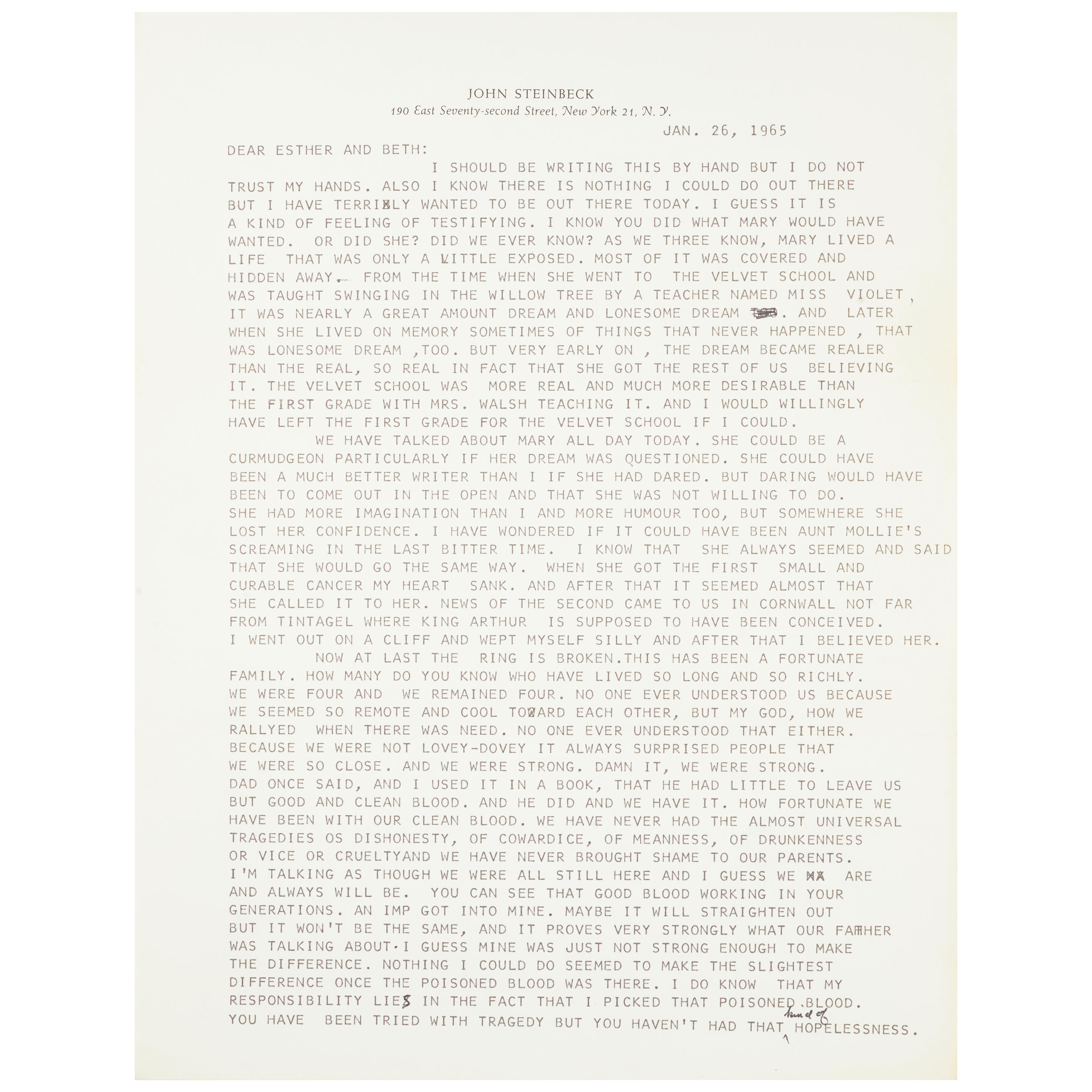

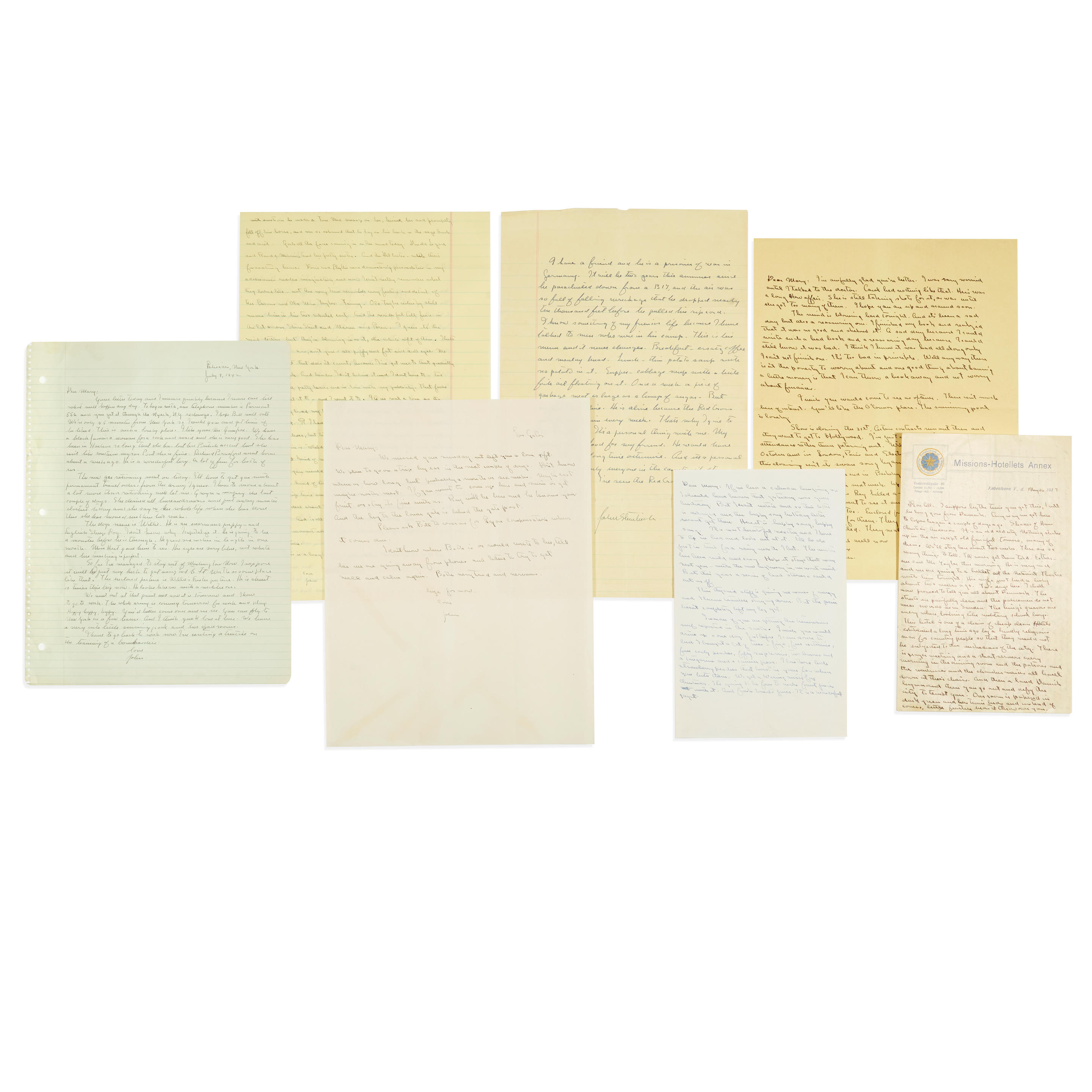

377 letters and postcards, most autograph but probably a quarter typed (particularly some of the later letters), from John Steinbeck to his younger sister Mary Steinbeck Dekker and other family members, discussing both personal and professional milestones over the decades, approximately 1000 pages, various sizes, various places including New York, Salinas, Mexico, and points in Europe, May 26, 1937 to October 21, 1964, most with original transmittal envelopes, in varying condition but generally good.

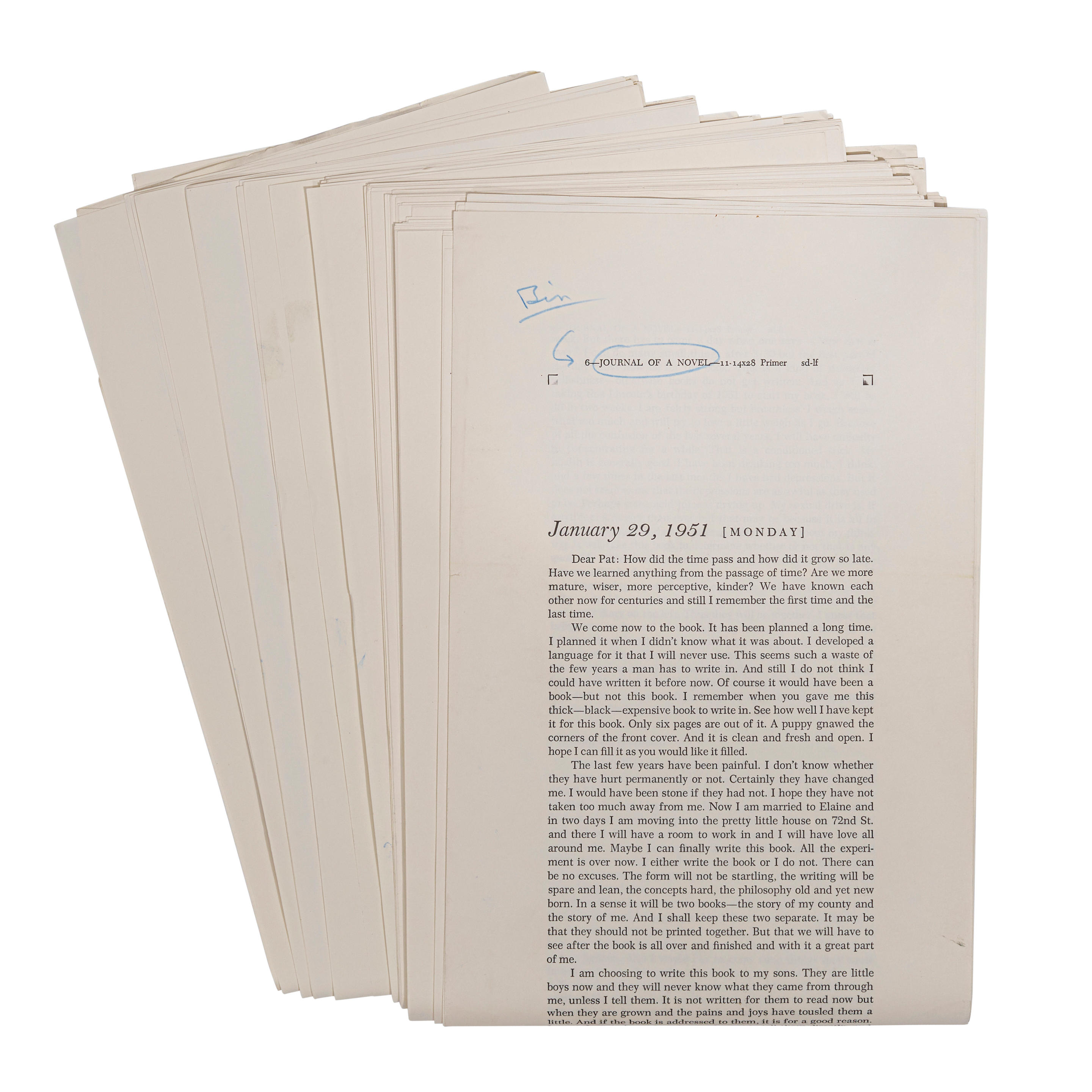

Over 300 of the letters are to Mary alone or to Mary and her husband Bill, a World War II pilot who disappeared over Italy in July of 1943. There are another 14 or so letters addressed to Mary, Beth and Esther, the three Steinbeck sisters, and sent in triplicate, and an additional 34 letters to Mary's daughter and son-in-law, Joan and David Heyler, most written during 1950-51 and many reporting on the progress of writing East of Eden. The collection is rounded out by assorted ephemera, notes and two typescripts, including a note to Mary from Pat Covici on the necessity of the title East of Eden.

THIS VAST CORRESPONDENCE FROM STEINBECK REPRESENTS THE MOST COMPLETE CATALOGUE OF HIS LIFE AND WORK AVAILABLE IN ONE COLLECTION. His sister Mary, being the closest in age to John, represented the author's closest family tie throughout his life, and their correspondence over nearly 30 years narrates the major life events in both his work life and his personal life. Steinbeck has been touted as a wonderful letter writer, and indeed the present collection bears that out. Charming and insightful, Steinbeck writes these very personal letters beginning when he and Carol were still living in Pacific Grove, through his breakup with Carol, moving to New York with Gwyn, the disappearance of Mary's husband Bill Dekker while he was fighting in World War II, the birth of his sons, his breakup with Gwyn, meeting Elaine, the growth of his sons, covering all the various successes and failures of his work, the openings, closings, finishing books, starting books, throwing away work, research, and all the rest.

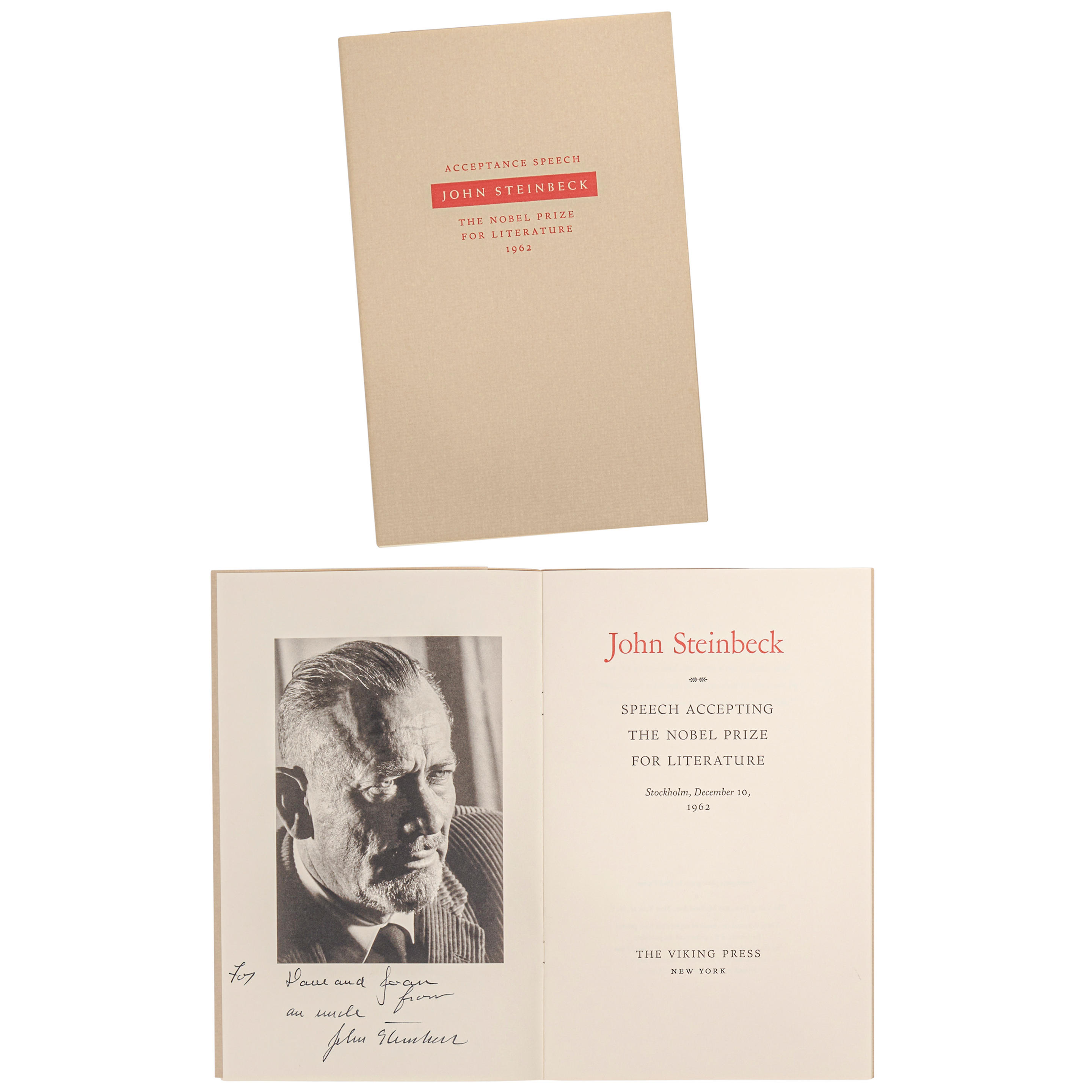

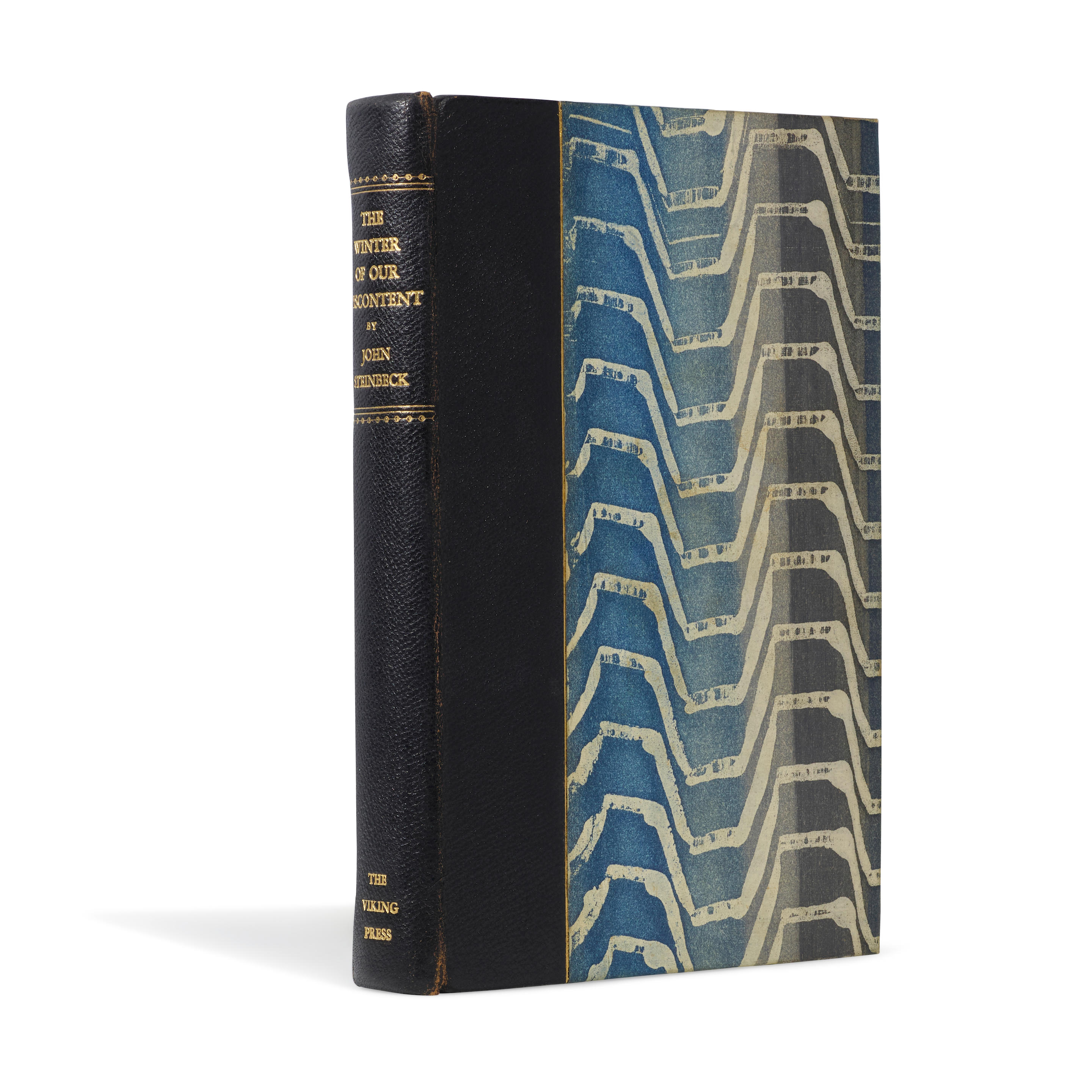

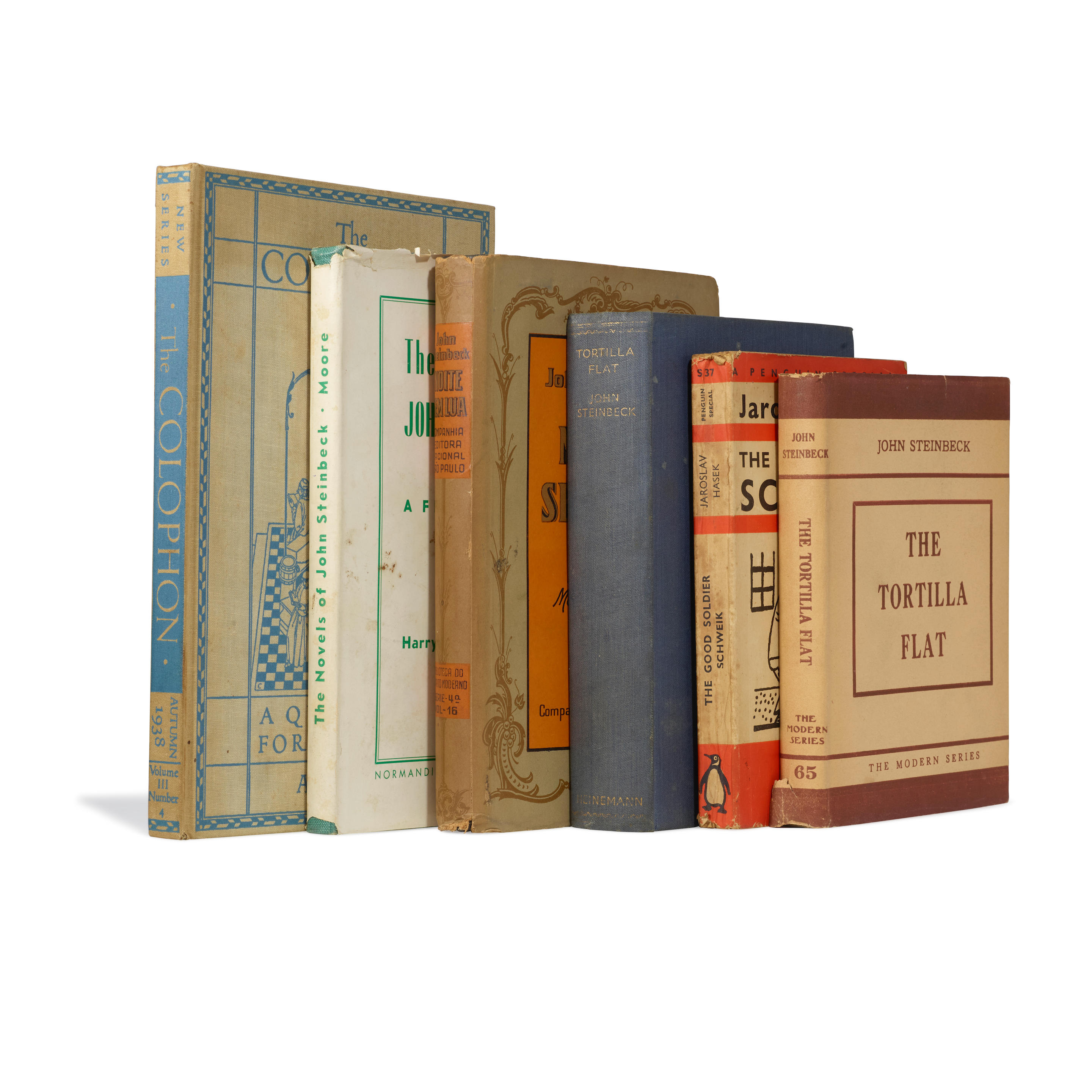

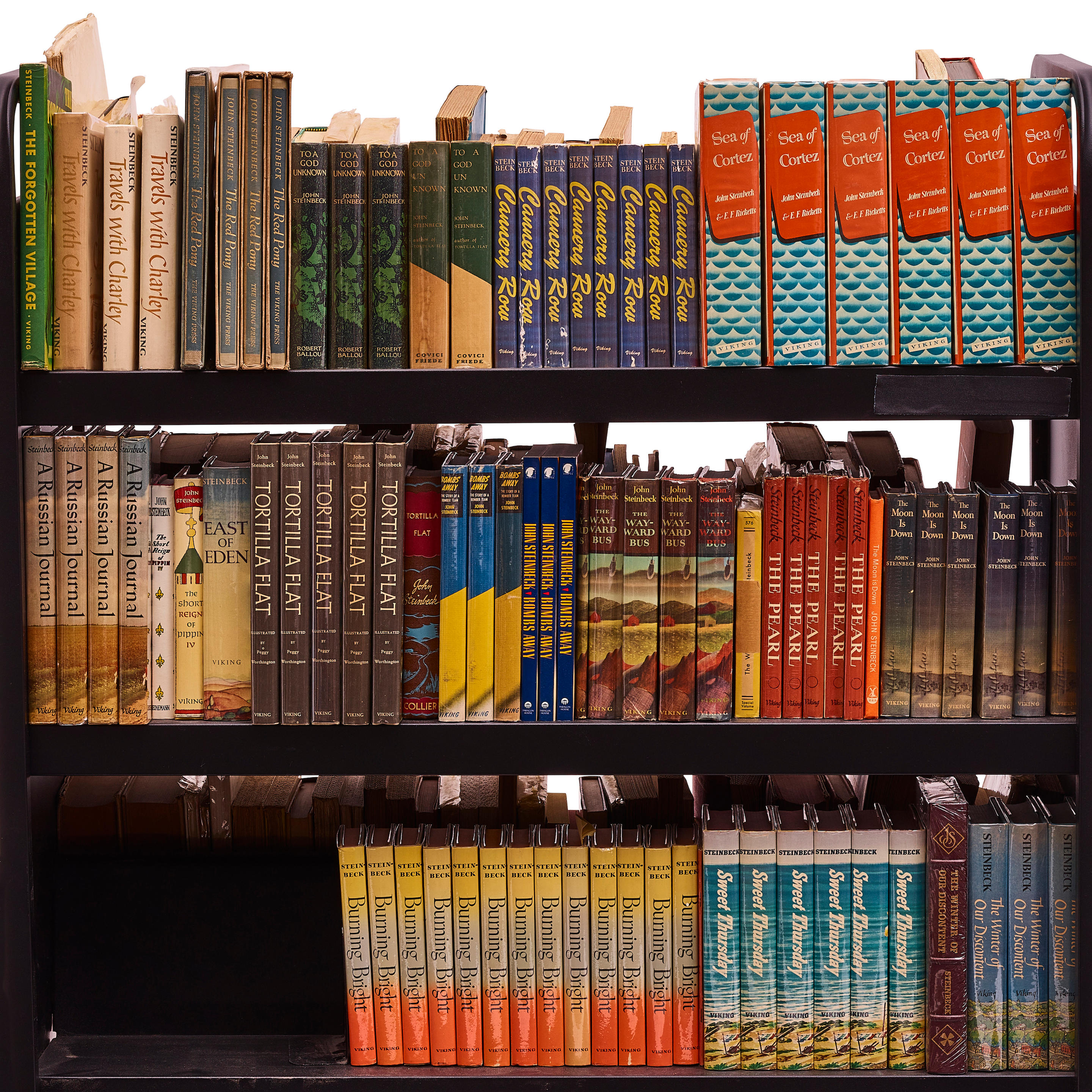

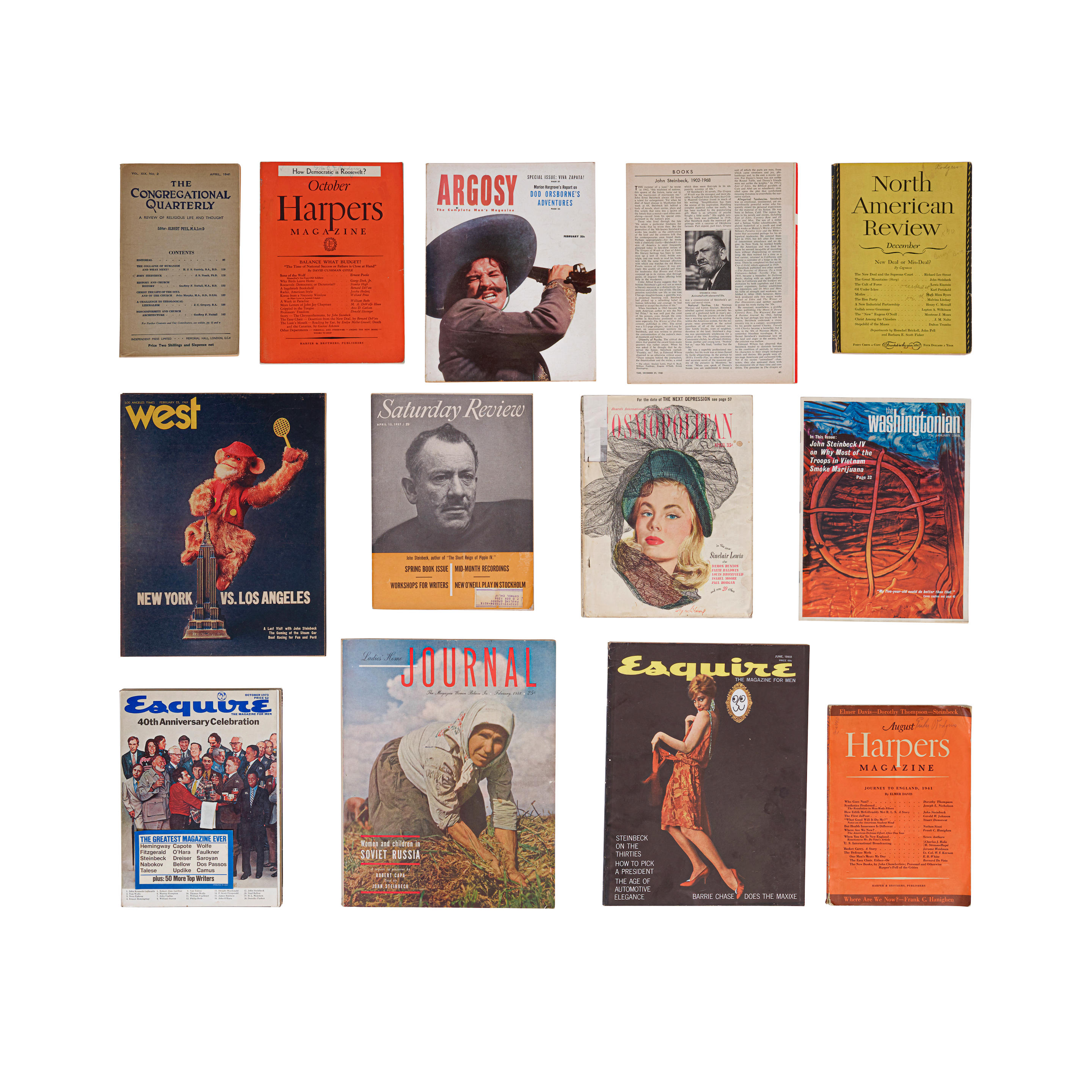

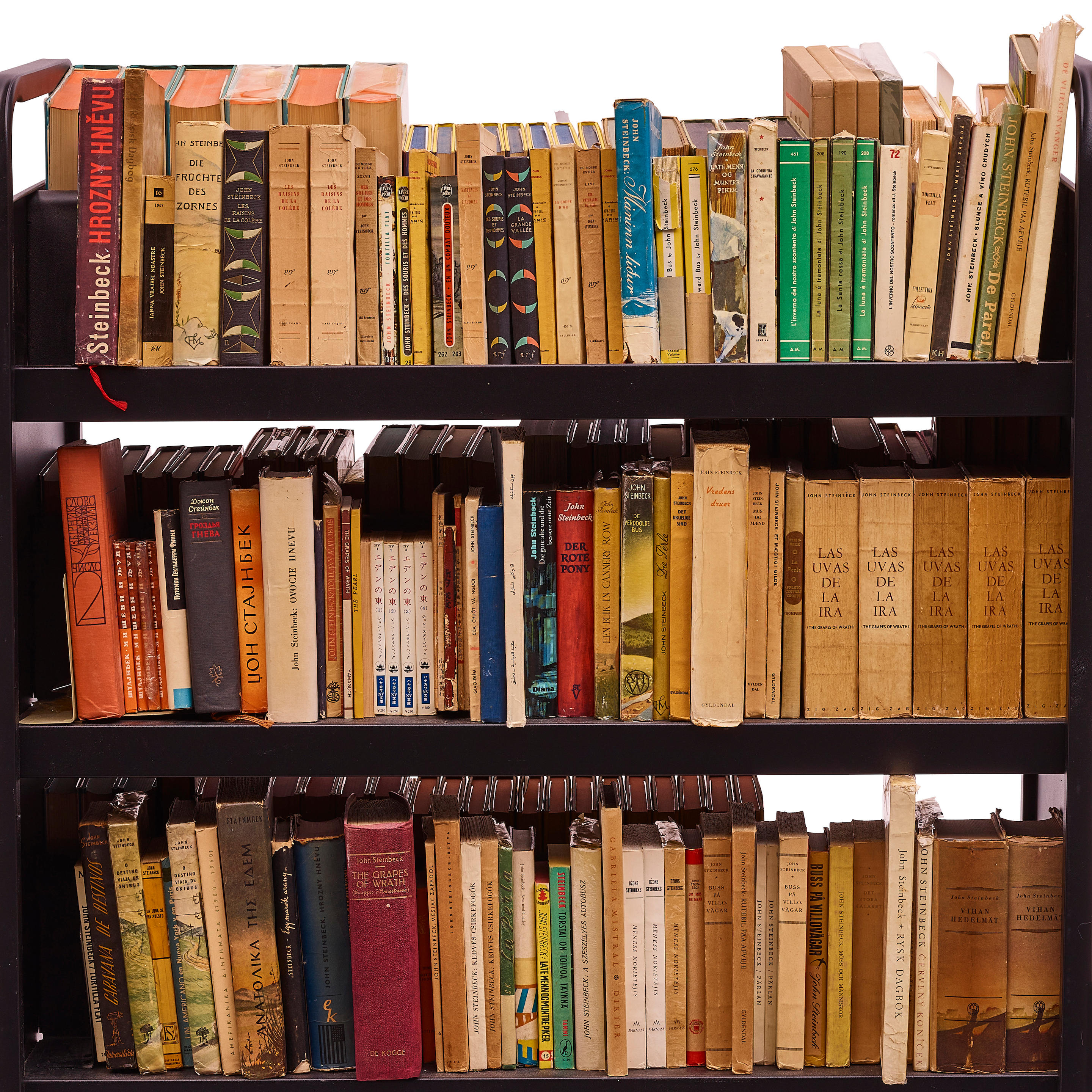

Aside from letters to Mary, there are also a number of letters to Esther and Beth, but of great interest are the letters to Mary's daughter Toni, and her husband David Heyler. Heyler was a fellow Stanford graduate, and in John's letters to Mary his fondness for David is evident. David was also very interested in book collecting, and Steinbeck enjoyed advising him and helping him in developing his collection. The letters from Steinbeck to the Heylers contain great Steinbeck bibliographical content, and document the transmission of many of the items in the current catalogue.

For a private writer, who famously didn't like his author biographies, and particularly not his author photos, perhaps the present collection of correspondence covering his most fruitful years as an artist are the closest we can come to autobiography.

Highlights are too numerous to catalogue, and he writes in a highly personal, rambling conversational style covering multiple important topics within a single letter. The results range from the quotidian to the sublime. Here are a few tidbits:

From December 12, 1940, writing to Mary and Bill, remembering Salinas, "I think it was Monday morning in Salinas – grey, cold sky and me in bed looking out the rusty screen and dreaming the week. And you practicing the piano downstairs and then to school in the red brick high school, dark halls and into the dark class rooms...and the teachers as horrified or moreso, at having to associate with us as we were to have to listen to them... This is the kind of wind when you remember things. I remember Miss Westerman – young, pretty and excited. I thought I got a liking for sociology pretty quickly when really I was only in love with the teacher... Gosh all the faces coming in on the wind today. Donald Legere and Ronald Matrine and his pretty sister. And the Del Contes with their fascinating house. Doris and Phylis were donminating personalities in my adolescence ridden imagination and now I can't really remember what they looked like – not the way I can remember every feature and detail of the Bacons and Old Man Taylor... in his two wheel cart. And the wonderful tall fence in the lot across Stone Street... I guess it's the wind today but they're blowing in on it, the whole cast of them. I hate to see any of them now don't you – all puffy and fat and dull eyed. We too of course but that doesn't count, because I've got used to that gradually... is all the sense of being at home just a myth. I've never been except in a moment now and then. I wonder if it just isn't true. I grow more restless all the time. This is a long and pointless letter. Maybe it's the wind has done it. Love- John."

April 24, 1943, a letter to Mary begins asking for information regarding her husband Bill and a land mine, then continues, "... I'm working for O.W.I. (Office of War Information) and the War Dept and the Air Forces. Pascal wants to go to England in May to make a picture and I may do it... The air force wants me to do a book on high and low altitude bombing and I'll probably do that too. It's very funny – on the strength of that child's book I've turned into an authority and I can't even fly a ship... But I'll probably get some precision bombing over France, and some ship bombing over Kiska... But probably none of it will happen. All plans get bogged down somewhere. I spent the morning with Henry Kaiser and did a broadcast to Australia this afternoon... when I finish this letter I have to write a broadcast to Sweden... Love to you all, and please do write, John."

October 20, 1943, a letter to Mary, there is little information regarding Bill, but there is no reason to be alarmed as of yet, "I haven't written much. I knew I could get things in the columns [reporting for the Herald] that I couldn't in letters, and I've never got over a sense of outrage at censorship even though it may be necessary. Frankly, I couldn't find out anything about Bill. I enclose a letter from his Commanding General. By now you must know where it happened. I couldn't even find out about that. And if I could have, they wouldn't have let me write it, even to you. Some of the restrictions seem very stupid to me... Love to you and I wish we could help you. John."

December 1, 1943, again on censorship and General Patton: "I'm almost through with the press stuff. The censorship on this side is so much worse than overseas and I'm sick of having my copy end up in Washington. They seem to be keeping information from Americans and from Germans. They cut out absurd things. This Patton story is one of their bumbles. We knew it when it happened – everyone in the area knew it and it was bound to get out. If they had only let us tell it straight they would have kept public confidence. Patton of course should have been removed months ago. I think he is nuts and is not a good field commander. And the thing that got out was just one of many incidents. But anyway... Love, John."

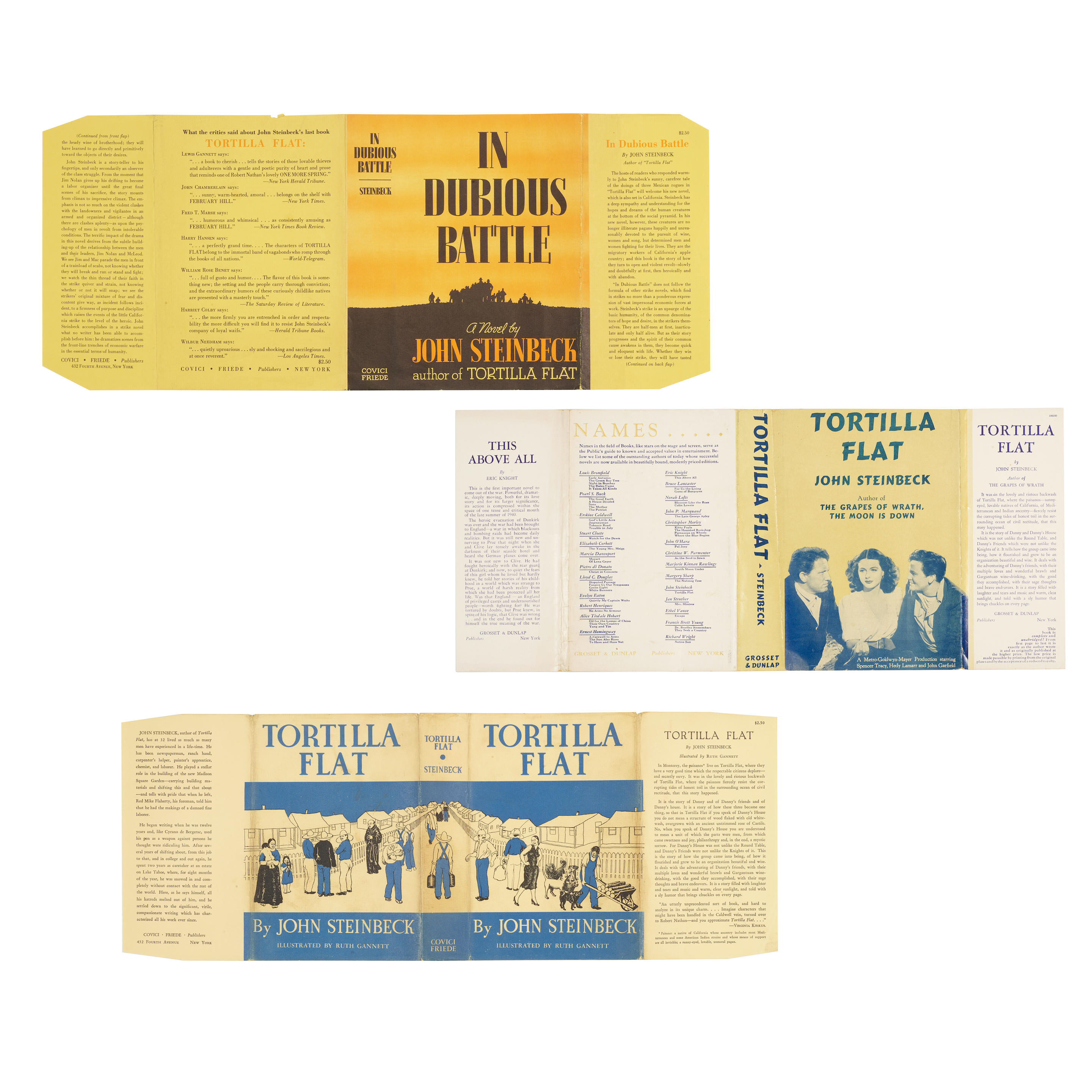

January 30, 1946: "Just a note... Viking is getting out a new edition of Tortilla Flat and Peggy Best is doing paintings for it. Anyway she is going out to Monterey and will stop at the lodge. But if she calls you, will you show her some of the old places? ... We're getting pretty well set on the wizard – Frank Loesser is doing music and lyrics, Logan or Abbot directing, Stuart Chaney for sets and Robbins for choreography... This was just a note anyway. Love. John."

December 29, 1947, to Mary, possibly the first mention of his East of Eden research, "Your presents arrived and were over whelming. Tom looks very fine in his suit... I've been trying to sort out my time. I have to write the United Nations childrens appeal, and after that do the script of Cannery Row and the I want to go west for a month or so probably some where about the 1st of Feb or thereabouts. I have to dig up a lot of data and revisit a lot of places. Maybe you would like to go to some of the places with me?... Happy New Year and thanks for the very fine presents. Love, John."

August 19, 1948 to Mary letting her know that Gwyn has left him: "I haven't written to Beth because I don't want to spoil her trip... But the sad truth is Gwyn and I are splitting up. I don't know what caused it but for about four years there has been an increasing hostimilty and tension in her and she wants to separate from me. There is no one else involved on either side. I do not seem to be good for women but in this case I have tried very hard... It is all very friendly and civilized, except that it is nuts... She loves New York and will stay here, and I'll go back to P.G. for a time anyway and live in the cottage and perhaps fix it up a little. I have so much work to do that I can't take the time to be upset... Must start building again. I think I have had my last wife though. Two fails out of two is enough to indicate it is not my metier... It will probably be all right. There is no good howling about it anyway and you get used to anything. Only it does seem so needless. See you soon. Love, John."

After meeting Elaine, they have settled into a new house, and he has begun working on his new novel [East of Eden] in earnest: "I am working every day on my new novel – notes and false starts which seem always to be necessary. But I think it is going to be good. It's a fine clear theme and it will be a very long book. It may take a long time to write and I hope it does...."

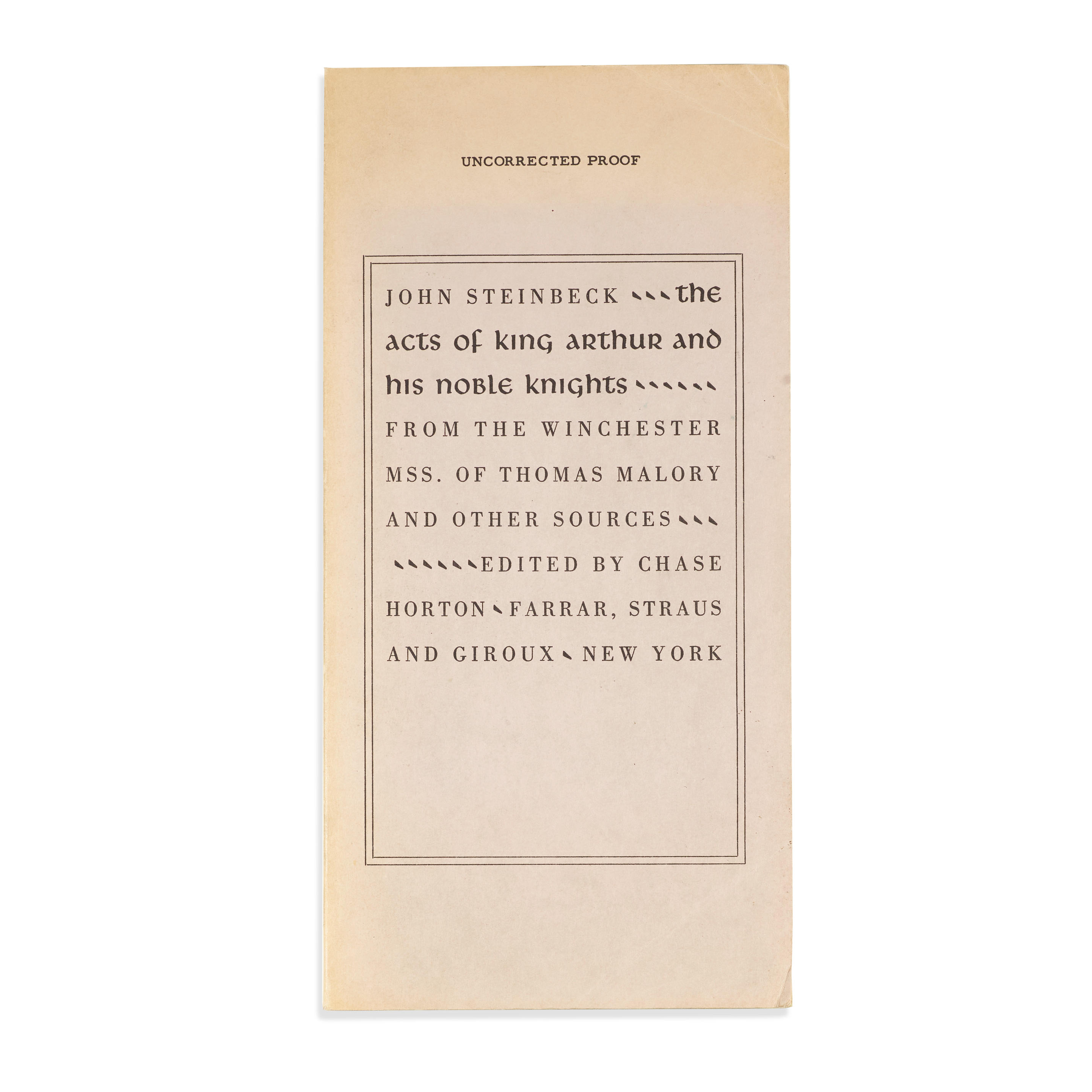

Beginning in 1956, Steinbeck began work on his translation of Malory's Arthur, which he always considered to be Mary's book since they had discovered the stories together which had become part of the fabric of their childhood. Many of the letters of this period relate to his own quest to first research and then write the book, which he would for various reasons, not finish within his lifetime.

On February 13, 1957, he writes: "Dear Mary, Just a note. That's the way they all start. I think my whole body of work began with 'just a note'. I nearly finished with the first of three volumes of Malory – that is very rough translation – first finished Gareth and starting the great Isolde or Sir Tristram de Lyones. That is a long one. By the time you get here I will have roughly 700 pp of manuscript or about one half of my book – that is with out the opening essays to each story. Then I am going to put it aside... I'm going to take a long time preparing it. After all I've waited 40 years to start. But I'll like you to look over what I have done when you get here. See if I have captured the old magic..."

As they grow old, the letters begin to deal with their mortality, as well as his legacy. On September 24, 1958, following Mary's first surgery, John writes to her: "You say that you don't care how long you live and that is a correct attitude for who is to say what constitutes a long life. Surely duration is not the ruler. Keats lived a very long life and old Mrs Williams a very short one. If you lived to be a hundred it would be a short life if it were not a rich one. I don't know how long in point of time I have, and I confess that sometimes I have a weary wish that it were over like a bad second act and the curtain down, but mostly I want it to be long in episode and feeling and experience, even bad experience. I am going to goose it in that direction and I sense that you are too...."

The letters continue through Mary's death, and the archive itself continues well beyond that. This rich trove of primary Steinbeck material offers future researchers an enormous opportunity for a deeper understanding of John Steinbeck and his work, and of the heart of 20th-century literature.

377 letters and postcards, most autograph but probably a quarter typed (particularly some of the later letters), from John Steinbeck to his younger sister Mary Steinbeck Dekker and other family members, discussing both personal and professional milestones over the decades, approximately 1000 pages, various sizes, various places including New York, Salinas, Mexico, and points in Europe, May 26, 1937 to October 21, 1964, most with original transmittal envelopes, in varying condition but generally good.

Over 300 of the letters are to Mary alone or to Mary and her husband Bill, a World War II pilot who disappeared over Italy in July of 1943. There are another 14 or so letters addressed to Mary, Beth and Esther, the three Steinbeck sisters, and sent in triplicate, and an additional 34 letters to Mary's daughter and son-in-law, Joan and David Heyler, most written during 1950-51 and many reporting on the progress of writing East of Eden. The collection is rounded out by assorted ephemera, notes and two typescripts, including a note to Mary from Pat Covici on the necessity of the title East of Eden.

THIS VAST CORRESPONDENCE FROM STEINBECK REPRESENTS THE MOST COMPLETE CATALOGUE OF HIS LIFE AND WORK AVAILABLE IN ONE COLLECTION. His sister Mary, being the closest in age to John, represented the author's closest family tie throughout his life, and their correspondence over nearly 30 years narrates the major life events in both his work life and his personal life. Steinbeck has been touted as a wonderful letter writer, and indeed the present collection bears that out. Charming and insightful, Steinbeck writes these very personal letters beginning when he and Carol were still living in Pacific Grove, through his breakup with Carol, moving to New York with Gwyn, the disappearance of Mary's husband Bill Dekker while he was fighting in World War II, the birth of his sons, his breakup with Gwyn, meeting Elaine, the growth of his sons, covering all the various successes and failures of his work, the openings, closings, finishing books, starting books, throwing away work, research, and all the rest.

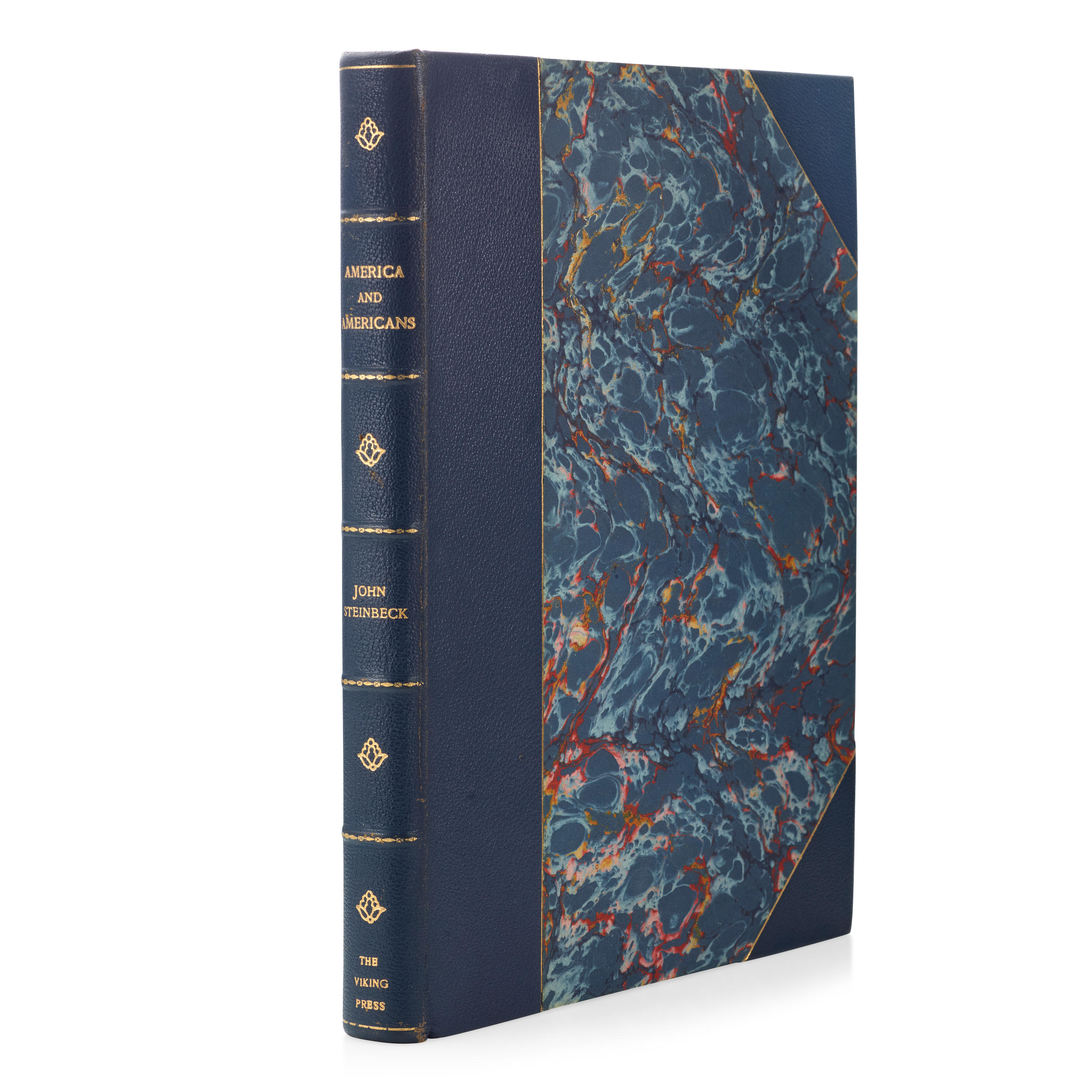

Aside from letters to Mary, there are also a number of letters to Esther and Beth, but of great interest are the letters to Mary's daughter Toni, and her husband David Heyler. Heyler was a fellow Stanford graduate, and in John's letters to Mary his fondness for David is evident. David was also very interested in book collecting, and Steinbeck enjoyed advising him and helping him in developing his collection. The letters from Steinbeck to the Heylers contain great Steinbeck bibliographical content, and document the transmission of many of the items in the current catalogue.

For a private writer, who famously didn't like his author biographies, and particularly not his author photos, perhaps the present collection of correspondence covering his most fruitful years as an artist are the closest we can come to autobiography.

Highlights are too numerous to catalogue, and he writes in a highly personal, rambling conversational style covering multiple important topics within a single letter. The results range from the quotidian to the sublime. Here are a few tidbits:

From December 12, 1940, writing to Mary and Bill, remembering Salinas, "I think it was Monday morning in Salinas – grey, cold sky and me in bed looking out the rusty screen and dreaming the week. And you practicing the piano downstairs and then to school in the red brick high school, dark halls and into the dark class rooms...and the teachers as horrified or moreso, at having to associate with us as we were to have to listen to them... This is the kind of wind when you remember things. I remember Miss Westerman – young, pretty and excited. I thought I got a liking for sociology pretty quickly when really I was only in love with the teacher... Gosh all the faces coming in on the wind today. Donald Legere and Ronald Matrine and his pretty sister. And the Del Contes with their fascinating house. Doris and Phylis were donminating personalities in my adolescence ridden imagination and now I can't really remember what they looked like – not the way I can remember every feature and detail of the Bacons and Old Man Taylor... in his two wheel cart. And the wonderful tall fence in the lot across Stone Street... I guess it's the wind today but they're blowing in on it, the whole cast of them. I hate to see any of them now don't you – all puffy and fat and dull eyed. We too of course but that doesn't count, because I've got used to that gradually... is all the sense of being at home just a myth. I've never been except in a moment now and then. I wonder if it just isn't true. I grow more restless all the time. This is a long and pointless letter. Maybe it's the wind has done it. Love- John."

April 24, 1943, a letter to Mary begins asking for information regarding her husband Bill and a land mine, then continues, "... I'm working for O.W.I. (Office of War Information) and the War Dept and the Air Forces. Pascal wants to go to England in May to make a picture and I may do it... The air force wants me to do a book on high and low altitude bombing and I'll probably do that too. It's very funny – on the strength of that child's book I've turned into an authority and I can't even fly a ship... But I'll probably get some precision bombing over France, and some ship bombing over Kiska... But probably none of it will happen. All plans get bogged down somewhere. I spent the morning with Henry Kaiser and did a broadcast to Australia this afternoon... when I finish this letter I have to write a broadcast to Sweden... Love to you all, and please do write, John."

October 20, 1943, a letter to Mary, there is little information regarding Bill, but there is no reason to be alarmed as of yet, "I haven't written much. I knew I could get things in the columns [reporting for the Herald] that I couldn't in letters, and I've never got over a sense of outrage at censorship even though it may be necessary. Frankly, I couldn't find out anything about Bill. I enclose a letter from his Commanding General. By now you must know where it happened. I couldn't even find out about that. And if I could have, they wouldn't have let me write it, even to you. Some of the restrictions seem very stupid to me... Love to you and I wish we could help you. John."

December 1, 1943, again on censorship and General Patton: "I'm almost through with the press stuff. The censorship on this side is so much worse than overseas and I'm sick of having my copy end up in Washington. They seem to be keeping information from Americans and from Germans. They cut out absurd things. This Patton story is one of their bumbles. We knew it when it happened – everyone in the area knew it and it was bound to get out. If they had only let us tell it straight they would have kept public confidence. Patton of course should have been removed months ago. I think he is nuts and is not a good field commander. And the thing that got out was just one of many incidents. But anyway... Love, John."

January 30, 1946: "Just a note... Viking is getting out a new edition of Tortilla Flat and Peggy Best is doing paintings for it. Anyway she is going out to Monterey and will stop at the lodge. But if she calls you, will you show her some of the old places? ... We're getting pretty well set on the wizard – Frank Loesser is doing music and lyrics, Logan or Abbot directing, Stuart Chaney for sets and Robbins for choreography... This was just a note anyway. Love. John."

December 29, 1947, to Mary, possibly the first mention of his East of Eden research, "Your presents arrived and were over whelming. Tom looks very fine in his suit... I've been trying to sort out my time. I have to write the United Nations childrens appeal, and after that do the script of Cannery Row and the I want to go west for a month or so probably some where about the 1st of Feb or thereabouts. I have to dig up a lot of data and revisit a lot of places. Maybe you would like to go to some of the places with me?... Happy New Year and thanks for the very fine presents. Love, John."

August 19, 1948 to Mary letting her know that Gwyn has left him: "I haven't written to Beth because I don't want to spoil her trip... But the sad truth is Gwyn and I are splitting up. I don't know what caused it but for about four years there has been an increasing hostimilty and tension in her and she wants to separate from me. There is no one else involved on either side. I do not seem to be good for women but in this case I have tried very hard... It is all very friendly and civilized, except that it is nuts... She loves New York and will stay here, and I'll go back to P.G. for a time anyway and live in the cottage and perhaps fix it up a little. I have so much work to do that I can't take the time to be upset... Must start building again. I think I have had my last wife though. Two fails out of two is enough to indicate it is not my metier... It will probably be all right. There is no good howling about it anyway and you get used to anything. Only it does seem so needless. See you soon. Love, John."

After meeting Elaine, they have settled into a new house, and he has begun working on his new novel [East of Eden] in earnest: "I am working every day on my new novel – notes and false starts which seem always to be necessary. But I think it is going to be good. It's a fine clear theme and it will be a very long book. It may take a long time to write and I hope it does...."

Beginning in 1956, Steinbeck began work on his translation of Malory's Arthur, which he always considered to be Mary's book since they had discovered the stories together which had become part of the fabric of their childhood. Many of the letters of this period relate to his own quest to first research and then write the book, which he would for various reasons, not finish within his lifetime.

On February 13, 1957, he writes: "Dear Mary, Just a note. That's the way they all start. I think my whole body of work began with 'just a note'. I nearly finished with the first of three volumes of Malory – that is very rough translation – first finished Gareth and starting the great Isolde or Sir Tristram de Lyones. That is a long one. By the time you get here I will have roughly 700 pp of manuscript or about one half of my book – that is with out the opening essays to each story. Then I am going to put it aside... I'm going to take a long time preparing it. After all I've waited 40 years to start. But I'll like you to look over what I have done when you get here. See if I have captured the old magic..."

As they grow old, the letters begin to deal with their mortality, as well as his legacy. On September 24, 1958, following Mary's first surgery, John writes to her: "You say that you don't care how long you live and that is a correct attitude for who is to say what constitutes a long life. Surely duration is not the ruler. Keats lived a very long life and old Mrs Williams a very short one. If you lived to be a hundred it would be a short life if it were not a rich one. I don't know how long in point of time I have, and I confess that sometimes I have a weary wish that it were over like a bad second act and the curtain down, but mostly I want it to be long in episode and feeling and experience, even bad experience. I am going to goose it in that direction and I sense that you are too...."

The letters continue through Mary's death, and the archive itself continues well beyond that. This rich trove of primary Steinbeck material offers future researchers an enormous opportunity for a deeper understanding of John Steinbeck and his work, and of the heart of 20th-century literature.

Try LotSearch and its premium features for 7 days - without any costs!

Be notified automatically about new items in upcoming auctions.

Create an alert