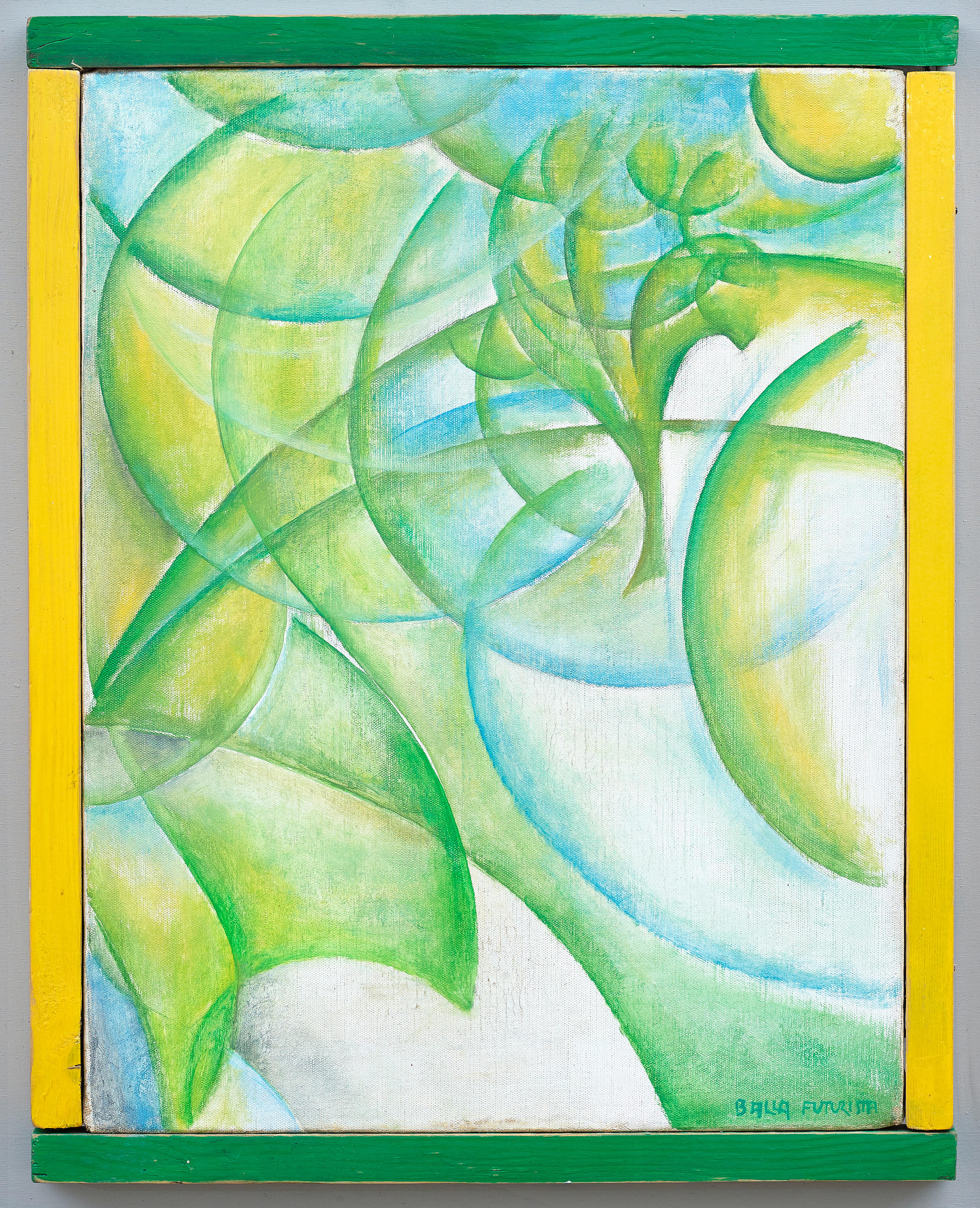

Giacomo Balla Automobile in corsa – studio signed and inscribed 'FUTUR BALLA' lower left pencil on paper 42 x 54 cm (16 1/2 x 21 1/4 in.) Executed in 1913-1914. This work is accompanied by two photo certificates; one signed by Luce Balla one by Elena Gigli, dated and numbered 17 November 2014, n. 571.

Provenance Casa Balla, Rome (Agenda n. 60 A) Prof. Enrico Fiorentino, Rome Thence by descent to the present owner Exhibited Mamiano, Fondazione Magnani Rocca, Giacomo Balla Astrattista Futurista, 12 September - 8 December 2015, no. 13, p. 56 (illustrated) Pontedera, Palazzo Pretorio, Tutti in moto. Il mito della Velocità in cento anni di arte, 9 December 2016 - 15 February 2017, p. 118 (illustrated) Catalogue Essay ‘Everything moves, everything runs, everything turns quickly. A figure is never motionless before our eyes, but it constantly appears and disappears ... [...] The gesture will no longer be a still moment of universal dynamism for us. Instead, it will be the dynamic sensation eternalised as such… We state that universal dynamism must be rendered as dynamic sensation’, the Futurists write in their manifesto of 1910. Ten years later Alfredo Petrucci emphasised Balla’s innovation: ‘one of the Futurist’s concerns was the duration of appearance. Before Boccioni realised his abstract plastic works, Balla focused on moving figures in some paintings and studies.’ In the spring of 1913 Giacomo Balla developed a study of the movement of swifts against the eaves of his house in Parioli, Rome. His little pieces of paper, where he simultaneously explored the analysis and synthesis of the movement of wings in flight, are countless, from notebooks to a variety of sheets. As his daughter Elica recalls, ‘there are swifts flying and partying around the roof of the house, so he busies himself studying their flight until late spring. It is a complex and hard task, as he not only wants to represent the succession of the image of birds as they fly, but also the moving lines of the watcher as, while observing, he slowly walks’. The six studies framed together at the Galleria Nazionale in Rome show the progress of Balla’s research; from the first studies made during his stay in Düsseldorf, to the drawings of a flock of birds that preclude his linee andamentali, concluding with his highly abstract composition of birds in flight, with the silhouette of a swallow moving right to left. The second issue addressed by Balla in the spring of 1913 is the disintegration of figures caused by movement and light; ‘movement and light destroy the materiality of figures’ (Manifesto Tecnico della Pittura Futurista, 1910). In the founding Futurist manifesto, Marinetti declared that ‘a racing car whose hood is adorned with great tubes, like serpents with explosive breath... A roaring car, that seems to ride on grapeshot, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace’ (ibid). The present work shows the first phase where, as Maurizio Fagiolo told me during the preparation of Balla’s catalogue raisonné, ‘cars always run from right to left, and the atmosphere gets thicker in the same direction, both in circular and diagonal forms. Faithful to scientific observation, Balla is conscious that the spectator’s eyes enter the picture from left to right. In this way, the impact between the represented object and the eye of the viewer is more dynamic’. Thus, the roof of the car, in scaling perspective on the left, is sharper than the triangles and wheels in motion, which are also present in the work Automobile + velocità + luce as seen in the Jucker Collection, housed in the Galleria Civica, Milan. Balla, who likened himself to Leonardo in the 15th century, next experimented by replacing the car with abstract speed, as exemplified by Abstract Speed - The Car has Passed, 1913, the colourful painting in the Tate Modern, London. How does Balla capture velocity through his use of line? Starting with specific studies, namely on the theme of relative motion, the flight of swallows, the interpenetration of light and the dynamism of a car’s motion, he reaches the line of speed, which he often defines as the ‘fundamental basis of my thought’. It is no coincidence that there are two notebooks where Balla develops the line of speed in more than fifty five studies. At times he c

Giacomo Balla Automobile in corsa – studio signed and inscribed 'FUTUR BALLA' lower left pencil on paper 42 x 54 cm (16 1/2 x 21 1/4 in.) Executed in 1913-1914. This work is accompanied by two photo certificates; one signed by Luce Balla one by Elena Gigli, dated and numbered 17 November 2014, n. 571.

Provenance Casa Balla, Rome (Agenda n. 60 A) Prof. Enrico Fiorentino, Rome Thence by descent to the present owner Exhibited Mamiano, Fondazione Magnani Rocca, Giacomo Balla Astrattista Futurista, 12 September - 8 December 2015, no. 13, p. 56 (illustrated) Pontedera, Palazzo Pretorio, Tutti in moto. Il mito della Velocità in cento anni di arte, 9 December 2016 - 15 February 2017, p. 118 (illustrated) Catalogue Essay ‘Everything moves, everything runs, everything turns quickly. A figure is never motionless before our eyes, but it constantly appears and disappears ... [...] The gesture will no longer be a still moment of universal dynamism for us. Instead, it will be the dynamic sensation eternalised as such… We state that universal dynamism must be rendered as dynamic sensation’, the Futurists write in their manifesto of 1910. Ten years later Alfredo Petrucci emphasised Balla’s innovation: ‘one of the Futurist’s concerns was the duration of appearance. Before Boccioni realised his abstract plastic works, Balla focused on moving figures in some paintings and studies.’ In the spring of 1913 Giacomo Balla developed a study of the movement of swifts against the eaves of his house in Parioli, Rome. His little pieces of paper, where he simultaneously explored the analysis and synthesis of the movement of wings in flight, are countless, from notebooks to a variety of sheets. As his daughter Elica recalls, ‘there are swifts flying and partying around the roof of the house, so he busies himself studying their flight until late spring. It is a complex and hard task, as he not only wants to represent the succession of the image of birds as they fly, but also the moving lines of the watcher as, while observing, he slowly walks’. The six studies framed together at the Galleria Nazionale in Rome show the progress of Balla’s research; from the first studies made during his stay in Düsseldorf, to the drawings of a flock of birds that preclude his linee andamentali, concluding with his highly abstract composition of birds in flight, with the silhouette of a swallow moving right to left. The second issue addressed by Balla in the spring of 1913 is the disintegration of figures caused by movement and light; ‘movement and light destroy the materiality of figures’ (Manifesto Tecnico della Pittura Futurista, 1910). In the founding Futurist manifesto, Marinetti declared that ‘a racing car whose hood is adorned with great tubes, like serpents with explosive breath... A roaring car, that seems to ride on grapeshot, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace’ (ibid). The present work shows the first phase where, as Maurizio Fagiolo told me during the preparation of Balla’s catalogue raisonné, ‘cars always run from right to left, and the atmosphere gets thicker in the same direction, both in circular and diagonal forms. Faithful to scientific observation, Balla is conscious that the spectator’s eyes enter the picture from left to right. In this way, the impact between the represented object and the eye of the viewer is more dynamic’. Thus, the roof of the car, in scaling perspective on the left, is sharper than the triangles and wheels in motion, which are also present in the work Automobile + velocità + luce as seen in the Jucker Collection, housed in the Galleria Civica, Milan. Balla, who likened himself to Leonardo in the 15th century, next experimented by replacing the car with abstract speed, as exemplified by Abstract Speed - The Car has Passed, 1913, the colourful painting in the Tate Modern, London. How does Balla capture velocity through his use of line? Starting with specific studies, namely on the theme of relative motion, the flight of swallows, the interpenetration of light and the dynamism of a car’s motion, he reaches the line of speed, which he often defines as the ‘fundamental basis of my thought’. It is no coincidence that there are two notebooks where Balla develops the line of speed in more than fifty five studies. At times he c

Try LotSearch and its premium features for 7 days - without any costs!

Be notified automatically about new items in upcoming auctions.

Create an alert